Ideas and resources to help you be a more thoughtful wine consumer, maker, and lover.

Happy Thanksgiving

Book of the year at Centralas.

We want you to know how grateful we are for all of you who read our posts, buy our wine, listen to the Organic Wine Podcast, and generally support the Centralas mission. Creating something new or different – like an ecological winery – is exciting and inspiring. But it often means going against the flow without a map… which can make us feel discouraged and lost. We couldn’t do what we do without your support.

It has been so encouraging to see the way our prickly pear wines have been embraced this year. We will be sold out by December (so if you’ve been thinking of trying them… now is your last chance), meaning they have been our best sellers of 2022!

Wendy and I drove from LA to Sonoma County recently. If you’ve done that drive it’s easy to zone out in California’s central valley since you can drive for 4 hours and only see 4 crops – grapes, almonds, cotton, and citrus. Seriously… that’s it. That’s where our almond milk, margarita mix, and t-shirts come from, folks.

But in the midst of those millions of acres of monoculture, this time I noticed a small orchard of prickly pear cactus of maybe 1 or 2 acres.

I couldn’t help but think that in 25 years that patch of prickly pears may be the only plants still thriving out of all those millions of acres… and that’s because they are the only plants that are currently thriving without massive amounts of irrigation and pesticides.

Making these wines is like being an investigative journalist at times. We have to dig deep into culture, history, science, psychology, and politics to uncover suppressed stories about excluded ingredients, forgotten techniques, and marginalized ideas. It’s a thrill to reveal some of these stories through our wine, and we hope we’re opening some eyes and hearts to new possibilities.

So, Thank you as well for the work you do in your own lives to further ecological awareness and support regenerative, biodiverse agriculture of all kinds. Keep up the great work!

If you want to be inspired by someone who is practicing agriculture in a way that will revolutionize the way you think about agriculture, check out this week’s episode of the Organic Wine Podcast with Mark Shepard, author of the book Restoration Agriculture – which is a top 10 Amazon bestseller in at least 3 categories.

With heartfelt gratitude,

Adam & Wendy

PS: There are some folks who have been especially supportive of Centralas in many special ways, and if you don’t know them, they are definitely worthy of encouragement and support:

Vinocity Selections, James Endicott – our distributor & friend who shares the same ecological values. Check out his other wines…. You can’t go wrong!

Chiara Shannon, Mindful Wine – Chiara has interviewed Adam for the Organic Wine Podcast as well as introduced us to many wonderful folks for some incredible collaborations. Interested in taking an ecological wine trip in the Columbia Gorge? Yoga and wine retreat in Paso Robles? Chiara does that and much more.

Wines Of Impact – our wine networkers, who we love to work with, and who extend our reach.

Viola Gardens, Jessica Viola – Jessica has featured Centralas multiple times at her amazing Topanga Canyon permaculture gardens, and she does stunning ecological landscaping.

The Westside Winos, Offhand Wine Bar and The Friend – our neighbors and friends who support Centralas and many other local wineries with great values, are instrumental in the Natural Action wine club, and also know something about art.

The wine shops and restaurants that buy our wine are too numerous to mention all, but here are some who have carried our wines repeatedly, hosted Centralas tastings, and continue to support us:

Esters in Santa Monica, Good Clean Fun in DTLA, Open Market in Koreatown, Café Birdie in Highland Park, Vintage Wine & Eats on Ventura Blvd, and last but definitely not least… South LA Wine Club, Highly Likely, Post & Beam, and Adams Wine Shop right here in West Adams/South LA.

And finally, we want to thank those who are the true foundation of Centralas… those responsible for caring and tending for the grapes and fruit we use to make wine:

The Galleano Family, who are responsible for the historic Lopez Vineyard and several other legacy vineyards.

Bill Shinkle, Tranquil Heart Vineyard, who is responsible for a variety of interesting and ecologically chosen grapes that we sometimes blend with prickly pears.

Also, let's not forget Patrick Kelly of Cavaletti Vineyards who might be the nicest guy alive and who provides a home for Centralas to make wines.

And life itself, the improbable and magical combination of water & light with a dash of stardust that found a corner of the universe to grow and dance and sing.

Thank you!!

Why Is Wine Important?

When I drank the wine that got me – that wine that had me groaning with pleasure at every sip and recalibrating my existence in terms of how I could make this elixir a bigger part of it – I thought I had made an amazing discovery.

One of the biggest illusions of looking out at the world through our eyes is that we think the universe revolves around us.

Excited by my new discovery, I plunged into study of the history and culture and craft of wine and winemaking. I read voraciously and tasted ravenously. The fascination deepened.

I began to buy grapes and make wine from them, chasing the ecstasy of that gateway sip. Each year I made more and more wine in my apartments, and then garages.

I began to write about wine. I wanted to share the joy and the pleasure that it brought me. Writing about it led me to want to learn more.

I began to work in wine, selling it. I got a sommelier pin. I got a WSET pin.

Finally, when I had a house with a yard, I planted my first vineyard. An “experimental vineyard” I called it.

I had no idea how to care for vines. In their fourth year they became so diseased that I had to pull them out.

I studied viticulture. I began to learn how to care for vines properly. I planted again. This time I didn’t call it experimental.

A year later I started a winery – Centralas – with a mission to reconnect consumers to the farming processes behind the wine they drink. I called it an “ecological winery.”

I started the Organic Wine Podcast at the same time. I wanted to connect to people who had the same level of passion about the entire ecosystem of wine. I wanted to build a library of knowledge about how to approach the farming and making of wine from an earth-first perspective.

And then it hit me.

An earth-first perspective is the perspective of the vines.

So I went out in the vineyard. I stood among the vines, looking. I sat down, listening. I laid down, feeling.

The vines were whispering to me.

“Finally, you idiot,” they said. “You thought you discovered a new favorite pleasure, but that was our lure. You thought you were learning and following your passion, but that was just us reeling you in. You thought you had planted a vineyard, but that was us landing you. You don’t farm wine. We farm you.”

My mind flew to the miles of vineyards and wineries that cover the globe, and I began to see them from the vines’ perspective.

Without being able to move, they had gathered rain from hundreds of miles away through irrigation systems, and brought resources from around the globe to sustain themselves… using us.

Without being able to speak, they had created blogs and podcasts and TV channels to promote themselves and their care.

They built schools and universities, businesses and industries, laws and infrastructure dedicated to their vitality and propagation.

I stand now in awe of the wisdom of vines.

They laugh at the hubris of the human-centeredness of names like Director of Vineyard Management or Vine Whisperer. They are the ones who have been managing and whispering.

Somm TV, ha! It’s Vine TV. Somms are just experts in their fishing lures (“humaning” lures?), part of the vines' PR team.

This is why wine is important. It’s the vine’s way of ensnaring us slow-witted humans into their service.

But it’s actually even bigger than that. Because the vines don’t see themselves as separate from their world like us humans do.

Vines see themselves as a process that is connected to all the other processes of life on earth. Caring for them implies caring for an entire planet.

And that’s why wine is really important. Because it teaches us that the way to make the best wine is to make the best earth.

Cheers!

Adam

PS: If you'd like to hear an audio version of this, check out this week's special two-chapter episode of the Organic Wine Podcast.

Promiscuous Viticulture: Crenshaw Cru Polyculture Winegarden Provides Inspiration

Crenshaw Cru – our estate polyculture winegarden in South LA - was born of necessity. I had to squeeze a very big love of growing things into a much too small urban yard.

I tried to overcome this discrepancy with dense, overlapping plantings. “Greedy for Green” might have been a good slogan for my approach to planting Crenshaw Cru in the beginning.

Ten years later, I’m realizing I may have stumbled on a form of vineyard polyculture that could provide vital resilience, and improved wine quality, in the face of climate change.

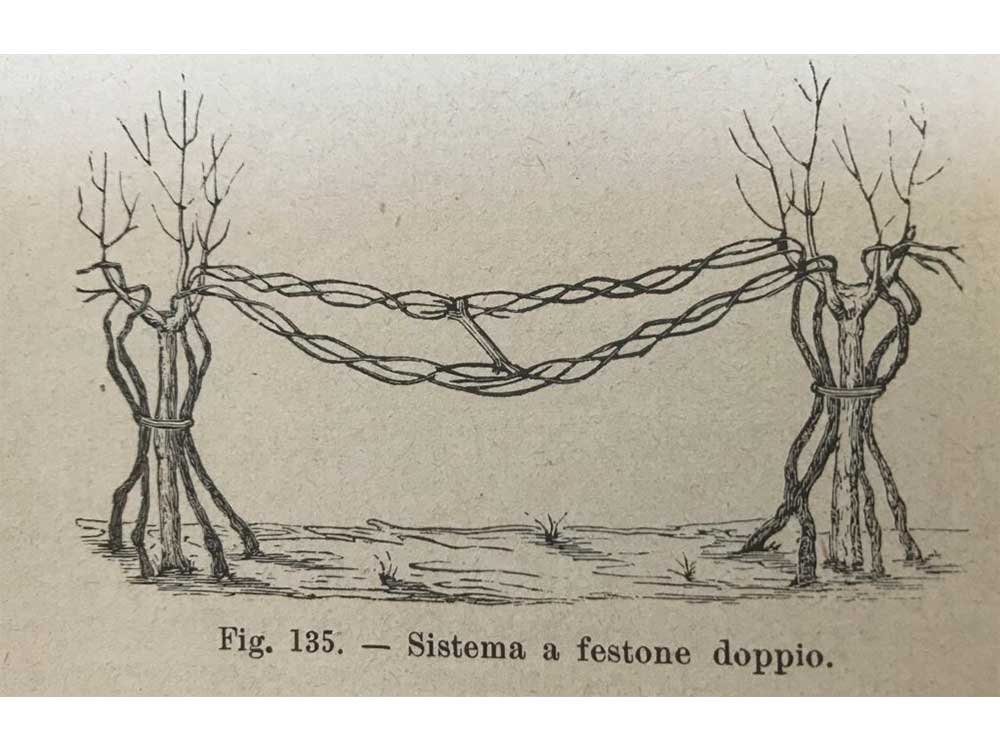

Tree Trellis. Credit

The Context of Promiscuous Viticulture

If you haven’t heard the term “agroecology” then you probably don’t listen to as many alternative farming podcasts as I do.

The truth is, though, that agroecology – as well as the related terms of agroforestry, silvopasture, alley cropping, and perennial polycultures, food forests, and winegardens (some of which we use to describe Crenshaw Cru) – are more than just trendy words used to describe ancient systems of farming (though they are that too).

All of these words are reactions against, and potential solutions to, the harm caused by industrial monocultures. There is a renaissance of thought happening right now in agriculture, and you will hear these words more and more.

Nature doesn’t do monocultures very often, and when it does they are usually temporary phases that serve as transitions after traumatic occurrences like fires, floods, landslides… or human folly.

Diversity is nature’s way of building adaptability and resilience – the ability to survive anything – into an ecosystem.

So when you remove diversity from an ecosystem and segregate 20 or more acres of one thing – like grapevines – you inevitably end up with a less adaptable and less resilient system (and, I would argue, a much less beautiful and enjoyable system as well).

Nature doesn’t have a favorite variety of grape either. Nature continues to select the grape that is best adapted to where its seed falls at that time in history. When historical conditions or the land itself changes, and that grape no longer thrives where it grew, nature grows another, different, better-adapted vine in its place. We can learn from nature by incorporating breeding and selection as an ongoing process in our idea of a vineyard.

All of this, by the way, is yet another reason to end our varietal obsession.

Diverse polyculture viticulture with animal. Credit: Jakob Philip Hackert

Re-Learning Viticulture

I’m in the process of re-thinking viticulture, and I’m inviting you to join me.

“Re-learning” viticulture is actually more accurate, because many of these ideas are the way that vines were grown for thousands of years before the industrial revolution and the conversion to intensive, large-scale, industrial viticulture and agriculture.

Instead of posts and wires, we used to grow vines on living trellises called “trees.” These living trellises also produced their own crops of nuts, fruit, and wood – depending on the tree – that added an additional crop to your vineyard besides just grapes, and therefore an additional source of sustenance and income.

These systems were often trained high, at average head height or above. This allowed for animals to graze beneath the vine-trees without being able to reach the fruit, and also allowed for the planting of smaller nut and berry shrubs, annual crops, and grains around the base of the vine-trees and in the rows.

Most viticulture around the Mediterranean (and likely globally) was practiced this way for thousands of years… really since grapes began to be cultivated. It has many names: Culture en Hautain, Joualle, Alberata (a shortened version of vite maritata all'albero – the vine married to the tree), and more broadly Cultura Mista or Cultura Promiscua.

This kind of viticulture is both haughty and promiscuous, apparently.

Rough design of Crenshaw Cru. Yellow lines are rows of vines. Green circles are larger trees that provide shade protection.

How Crenshaw Cru Fits In

While I didn’t plan ahead and plant trellis trees when I planted Crenshaw Cru (though I did in the most recent plantings), I did plant trees much closer than would be considered acceptable in a modern vineyard. Now that those trees have matured their shade presents an unexpected advantage.

Since the trees at Crenshaw Cru are all planted on the South and West sides of the yard, they have begun to shade the vines, at least in part, from the hottest sun of the day. As our hot climate heats up even more, this presents a way to modulate and slow the ripening of the grapes so that they ripen more gradually.

The shade of the trees, in other words, can act as a buffer against extreme heat… therefore potentially benefitting grape flavor development and ultimately wine quality.

There was a time in history when we wanted to get as much sun on the grapes as possible to ensure full ripeness. This hasn’t been an issue for a long time in California, and now the opposite is actually true: we want to solve the issue of extreme heat and ensure that ripening doesn’t happen too quickly.

We don’t need to trellis the vines on trees to make this happen. We could simply plant trees strategically throughout existing vineyards. Or if we are planting a new vineyard, we could design it in small plots with lines of tree buffers on the southern and western edges… just like Crenshaw Cru.

Both of these options would integrate trees into our idea of a vineyard while continuing to allow the ease of care for and harvest of the vines that modern vineyards maximize.

There are many other benefits from incorporating trees in and around vines. Trees drop their leaves and needles creating a beneficial, fungal mulch for any vines growing nearby. Trees pull additional nutrients out of the air and put them down in the soil where they provide for both themselves and any nearby vines. Trees can create a more moderate microclimate for the vines, protecting them from extreme winds, hail, and frosts. One experimental vineyard in France has even found, counterintuitively, a decrease in mildew pressure on the vines.

My suggestion for trees to use in California, and similar climates, would include pomegranates, figs, and olives - all of which are very drought tolerate, traditionally used in promiscuous viticulture, and produce their own crops. Also live oaks, ponderosa pines, possibly even sycamores would be equally suitable to our dry climate, and could get much larger and more shady than the fruit trees.

When we plant vines near trees, and vice versa, we’re doing a lot of wonderful things that may help provide solutions to problems that we caused. But ultimately, we’re just finally listening to nature and heeding its example.

Vines evolved to grow on trees. They are symbiotic, not parasitic. They are natural friends.

Maybe it’s time we reunited them. Maybe it’s what they’ve been asking for.

Cheers,

Adam Huss

Wild vine growing symbiotically in a forest ecosystem in North-Eastern United States.

Progress Report - Sept 2022

Since this is the progress report, I want to talk about a failure… because one of the ways we learn and progress is by failing. Sadly, it seems like we seldom change our behavior – even if we know what we should do – until we fail miserably and experience the pain and heartbreak of our actions.

So maybe I should say this was a learning experience. I will be a better farmer and winemaker because of it.

The short story is that I over-cropped the Crenshaw Cru Syrah vines.

There are multiple studies that disprove the idea that lower vineyard yields equals higher quality wine. I took these studies out of context and allowed each of the Syrah vines to grow far too many clusters of grapes.

It is true that if vineyard block A yields 3 tons per acre of Pinot Noir, and same vineyard block B yields 1.5 tons per acre, that does not mean that vineyard B produces superior Pinot Noir.

However, if each vine in same vineyard block C is allowed to produce 100 lbs of Pinot Noir… the grapes and vines in block C will definitely suffer. There is a limit to how much fruit a single vine can grow and ripen well.

This year I discovered this limit for the Crenshaw Cru vines.

Some of the grapes never went through veraison. When this happens, powdery mildew sets in and begins to impact the flavor and health of the grapes. I finally picked the grapes this week and had to leave a lot (half?) of the fruit on the ground. It was just not worth making into wine.

Half of what I was able to use I had to pick through grape by grape, saving only the whole, ripe grapes and discarding the rest that were either under-ripe or damaged by mildew. Harvesting 14 vines took an entire day… which, as a frame of reference, is absurd.

Additionally, I likely have impacted the health of the vines for next year’s vintage. They are stressed and depleted. They need to recuperate, and that takes seasons.

To be fair, part of my intent was actually to diminish the vines’ vigor, which I’m sure that I have. But there’s a difference between dieting and starving. I think I metaphorically starved them.

Because maybe part of my motivation was also greed… trying to extract as much wine as I could from this tiny vineyard.

Ironically, if I had been more modest in what I asked of the vines, if I had been less greedy, I would have ended up with more, healthier grapes.

The good news – the progress that I have to report – is that I’ve let the vines hold a mirror up to my humanity and show me how I can be a better person, and thereby a better caretaker of them. And I can share this lesson with you and others, so that you can hopefully learn from my mistakes and be better viticulturalists.

You did know that you are a viticulturalist, didn’t you?

There will be less Crenshaw Cru wine this vintage. But it will mean a lot more.

- Adam

Not all of the Crenshaw Cru syrah was ruined...

Good News From Around The World

Champagne Allows a New Hybrid Grape – Voltis – Into Its Cuvee

https://winencsy.com/new-permitted-wine-grape-variety-in-champagne-voltis/

Champagne has begun allowing a new hybrid variety of grape into its officially regulated mix. This is good for several reasons – and shows a way forward for other regions around the world. Bordeaux has allowed several new hybrids into its mix of grapes as well.

Pennsylvania Dept. of Agriculture Establishes Partnership with Lithuania To Share Organic Farming Knowledge

https://www.lancasterfarming.com/farming/organic/pennsylvania-forms-ag-relationship-with-lithuania/article_7dd879b0-fd39-11ec-9a17-57223d70d5e3.html

Most people don’t realize that “organic” has a Mecca, and it’s in Pennsylvania (home state of both Wendy and Adam!). The Rodale Institute in Kutztown, PA is the oldest organization dedicated to organic agriculture, and is responsible for originally popularizing “organic” back in the 1970’s. Now the state of PA is spreading the decades of acquired knowledge of organic agriculture internationally.

The Earth Is The Solution to The Our Problems

http://naturalclimatesolutions.org/

This amazing resource shows in detail, with case studies from around the globe, the many nature-based solutions to climate change, food and water security and cleanliness, and human health and well-being. This is a pro-business, pro-human, pro-nature look at how the earth provides win-win-win options to regenerating social, economic, and environmental conditions for everyone.

Organic Wine Podcast Episode Highlight

Adam interviewed two well-known scientists and best-selling authors – Anne Biklé and David R. Montgomery – for the Organic Wine Podcast. Their books – which we highly recommend everyone read - are actually quite optimistic about our ability to regenerate soil health, roll back climate change, significantly reduce carbon, and improve human health and vitality via regenerative agricultural practices. They report the science behind how this is done, and show example after example from around the globe proving that it works in every scenario and at scale. Adam’s interview is a great introduction to their work.

Thank you all for your support! It enables us to produce the Organic Wine Podcast, promote solutions to some big problems, and continue to make delicious wine that grows (literally and figuratively) from these regenerative values.

Cheers!

Adam & Wendy

PS. At harvest, sometimes organic pesticides stay on the grapes...

We’re Really Weird, Sorry.

If you’ve known Centralas for a while, we may have desensitized you to some eccentric, idiosyncratic, and even weird behavior.

We did this with the best intentions: we care about you and want the best for you. We envisioned the wine world we wanted you to live in, and we built that world for you.

But it’s not the real world.

The real world is… well, it’s many things, but it generally does not look out for your best interest. So it would be irresponsible for us to send you blithely forth into the dark woods of reality without preparing you for what you’ll encounter.

If your wine habit has developed or been influenced in any way by Centralas, it’s high time we sat you down and had “the talk” – the facts of wine life.

This isn’t an easy conversation for either of us, we know, but the discomfort we both feel now will be nothing compared to the chagrin you’ll experience someday soon if you think of us as “normal” and sally forth with the same expectations of every winery you meet.

Because - and it’s hard for us to admit this - we aren’t normal. We’re rather odd, actually, bordering on deviant if we’re being brutally honest.

So if you think of us as normal, you know what that says about you.

We know, we know… self-awareness is never easy. You may resist the idea that your family, I mean winery, is weird. So let us break it down for you.

1. We have a mission, and that mission isn’t about making moula.

Strange as it may sound, most folks don’t start wineries to make the world a better place. In fact most wineries don’t even really discuss the “Why?” behind their business.

If you start digging for a “Why?” out there in the real world, you may discover they don’t discuss it because there isn’t one… let alone having a reason for being that is founded on an ecological mission to protect & benefit your environment and community.

We make great wine to highlight how delicious an ecological approach to wine can be, and every decision we make is founded in how to heal and improve our world. If we’ve normalized this kind of aberrant business strategy for you, we’re very sorry.

2. We select vineyards based on their ecological excellence.

Because of the preeminence we give to where and how vineyards are farmed and to soil biology and to ecosystem integration and to awareness of irrigation practices and to chemical sprays and fertilizers used and to WHO is actually doing all this work and how they are treated, and because we choose to make wine from vineyards based on all this information (and not “Where can we find the cheapest Cab Sauv grapes?”), if you go out into the real world looking for similarly detailed information about winery vineyards with specifics about farming practices, and winemaking that is guided by this information… prepare yourself for disappointment. You will quickly discover a great yawning abyss of nothingness.

If you find anything at all, it will most likely be clichés about “distinctive terroir” or “ideal microclimate” or information about when vines were planted, how many acres, and what clones. Discussions of soil, if you find any, will be limited to “silty sand” or “calcareous clay.” Or, just as often, you’ll be redirected to information about the winemaking that happens in the winery.

And god forbid you expect to find any information about vineyard inputs anywhere, let alone on a wine label.

Please, don’t hold it against us. We’re weird. That’s what we’re trying to tell you.

3. And speaking of labels, we do a lot of abnormal things with ours.

Please don’t go out into the world looking for lists of ingredients used during winemaking, or empty bottle weights, or vineyard inputs. It just isn’t done.

Don’t embarrass yourself by asking a winemaker to tell you everything they added during winemaking. They really don’t want to tell you, and you often don’t want to know (especially if you’ve already drunk the wine).

Don’t question the rationale of that extra heavy wine bottle and if it has any correlation with quality or just with price.

Just pretend our labels and all of their information don’t exist. Your life will be easier, we promise.

4. We try to make wine that can only be made where we make it.

Look, you might as well know that our vision for wine is, by all measures, absurd. We believe that wine can be a drink that reflects the beautiful diversity of the world. We believe that wine can do this by using local, indigenous ingredients that thrive where they are grown without much human input at all. We believe in making wine that can only come from, in our case, Southern California.

The rest of the wine world that you experience when you leave the Centralas world is very happy to replicate the same kind of wine everywhere made from the same handful of varieties of non-indigenous grapes.

So when you go out, just act like a standard, monocultural French grape wine drinker. This will ensure your social success.

Never let it slip that you’ve drunk, and even quite enjoyed, wine made with wild prickly pears. Needles will scratch. Strangers will stare. Rooms will go silent. Pins will drop and be heard.

We want to spare you that kind of attention.

The truth is, unfortunately, that these are only the big ones. There are a lot of other ways in which we’re extremely weird.

We know we’ve put you at risk of social ruin by mis-calibrating your expectations in a myriad of ways by this fantasy world, this home, that we call Centralas.

We wish we could have given you a more realistic preparation for the real world. Alas, we can’t escape our own weirdness. It’s just who we are.

The other option, though, is that you don’t have to leave. Just stay here with us. Leave the real wine world for others.

And maybe, someday, our weird wine world will become a little less weird. Maybe.

with love and apologies,

Adam & Wendy

Lopez Vineyard - Dry-Farmed, Organic, Over 100 Years Old

Harvest Is Here

We got the call on Monday. Time to pick grapes from the dry-farmed, century-old, certified organic vines of Lopez Vineyard.

We started washing equipment, reserving a truck, canceling existing plans and making new ones.

Harvest is always a surprise. By mid-summer, we’re drifting along, lulled into dreaminess by the steady, quiet pull of the flow, not realizing we’re in a current that’s about to take us over the falls in a barrel. By the time we hear the roar, it’s too late to swim for shore. Nor do we want to. That plunge is half the fun.

But this harvest is more surprising than usual. It’s about 3 weeks earlier than the average.

I sent an email just before the Super Bowl this year, talking about how the abnormally early heat was causing an abnormally early start to the growing season. Well, harvest is following right along on the same abnormally early timeline.

Maybe “abnormal” is the wrong word to use, going forward. But I hate the term “the new normal.”

I think of life as like a child struggling to carry a large bucket full to the brim of water and almost too heavy to lift, spilling out joy and tragedy with each rushing, sloshing, stumbling step.

There are pros and cons to a growing season that starts early and finishes early.

One of the pros is that this means the grapes ripen and achieve maturity in the cooler earlier part of the year, before the crazy heat that usually comes in August and September here in Southern California. Milder weather allows for more even ripening, more balanced and complex flavors.

One of the cons is, well, climate change.

Lopez Vineyard

If you visited the Lopez Vineyard, you’d likely initially be underwhelmed. It looks like a giant vacant lot next to a freeway interchange that was supposed to be developed into a suburban neighborhood, but the plans got held up at City Hall and a bunch of viney weeds began to grow.

When you think of something that has lived through two world wars, dust bowls, great depressions, and two global pandemics, and everything that happened in between, you might expect something a little more… Grand? Noble? Monumental?

These are scrappy, scrubby little knee-high shrubs without trellising, nearly overwhelmed by weeds, hunkered down in the rocky sand. No thick trunks. No effusive displays of foliage. They look completely unremarkable.

Millions of people drive by them every year on two large freeways that were still decades away from being built when the vines were planted. The freeways overlook the vineyard, and most drivers overlook the vines entirely.

But we don’t want to make wine from anywhere else.

Like icebergs… and most of us… the vines only seem insignificant on the surface. Underneath they are deeply connected to history, culture, and all kinds of hidden aquifers (literal and metaphoric) that allow them to thrive.

As we stood among the 300 some acres of bush vines stretching out toward the base of the Angeles Mountains, we couldn’t help but be awed by their ability to abundantly produce their grapes year after year for over a hundred years.

Have you ever seen one of those displays about nuclear energy? A pound of dirt in a glass box has a caption something like, “If we could release the energy in this pound of dirt, we could power a city of a million people for a week.”

These vines make me think they have found the secret to unlock that energy.

The Lopez Vineyard is pruned each year. Other than that the vines are not watered by anything but the 5-10 inches of winter rains and underground aquifers, nor are they sprayed or fertilized with anything.

Yet every year they offer up around 300 tons of grapes. They are a true Giving Tree.

As wonderful as the vines themselves are, it would be unfair not to give credit to the viticultural wisdom of the humans who planted them originally.

The folks who planted Lopez Vineyard (circa 1912-1916) knew the heat and aridity would keep the pressure from mildews, mold, and insect pests at a minimum. They knew that, despite the dry climate, runoff from the nearby mountains would provide a reliable source of groundwater just a few feet down. They knew that the rocky, sandy soil would prevent these own-rooted vinifera vines from succumbing to root pests and rots.

And they knew that all of these factors gave just enough to allow the vines to live with very little human input, but not too much, so that the vines would have to struggle and overcome these environmental stresses, and this would produce delicious wine for over a century.

Hats off to those folks.

And hats off to these folks. They picked the Zinfandel grapes that Wendy and I spent the rest of the day processing yesterday. They stooped and crouched and picked about two acres, 1.5 tons of grapes, by hand with no knives, hooks, pruning shears or tools of any kind, in less than 2 hours.

The 2022 grapes are now in the winery and already in the process of becoming a couple different wines. We are attempting a 00000 wine this year.

You may have heard of 00 (zero-zero) wine. It stands for nothing added, nothing taken away… as in no ingredients used other than grapes, and no filtering or fining of any kind.

00000 takes this to another level: zero additives in the vineyard (no sprays nor fertilizers), zero irrigation, zero additives in the winery (just grapes), no filtering nor fining, AND zero exploitation of humans to produce the wine.

We aren’t purists. It’s more that we love a challenge.

We’re going to monitor the wine closely, and we may add sulfur if we think it is necessary to prevent the wine from turning to vinegar or spoiling in some other way. Now that we have a sense of the cultural history that we've become a small part of, we've begun to really not want to screw it up!

We’ll be bottling the 2021 Lopez Vineyard Zinfandel in about a month, and it will be available later in the fall. It’s a massive, succulent red that also tastes fresh and vibrant. We think you’ll love it. (It's a quadruple zero... we did add a little sulfur.)

The Future of Wine is Change: Re-Thinking Our Varietal Obsession

“What’s the grape variety?” is a question I’ve begun to hear a lot.

It’s my fault. In 2021 I decided to stop listing grape varieties on Centralas’s wine labels.

Grape variety is so fundamental to our understanding of wine in the 21st Century that its importance is taken for granted. I knew I was setting myself up to have nuanced conversations that might only lead to confusion and frustration with people who just want to know what they’re drinking.

(Of course this begs the question: Does knowing the name of a grape variety actually help you know what you’re drinking, or is it a misleading and limiting label that inhibits your understanding?)

I didn’t knowingly embark upon this Quixotic exercise in futility because of some sado-masochistic bent. I did it because of climate change.

Let me set this up a bit.

We started labeling wine by variety in the US only about 70 years ago. For eons prior to the 1950s, i.e. for the vast majority of wine history, specific grape varieties certainly had names but the wine was not named by grape variety.

Wine didn’t get named according to grape variety for all this time for some very good reasons.

First, most wine was made with a blend of grapes, and often other fruits, herbs, flowers, roots, honey, etc. Wine as a single grape variety beverage has really just been a recent fad, and may soon be (if my crystal ball isn’t out of whack) a passing fad.

Wine ingredients reflected local abundance and cultural practices. The purpose of wine was not to be a luxury commodity, but to preserve and add value to growing seasons in agricultural societies.

Diversity in agriculture was a pre-industrial way to have crop insurance. Planting a dozen different varieties of grapes ensured that even if you had a late frost, or a rainy summer, or an early snow and lost some potential harvest because of harm to some of the vines, you’d have other varieties of grapes that had later bud break, greater mildew resistance, or early ripening to beat these weather uncertainties. If you also had a diversity of fruit trees, berry bushes, and bees, your chances of having something to preserve with fermentation increased even more.

Also, implicit in not naming by grape variety is a perspective that views wine as a process and culture, rather than as a product and commodity.

Even in the US, vineyards planted in the 1800’s were often a variety of a dozen or more grapes. Some of these vineyards still exist because they were planted at a time when you had to plant ecologically – that is, in a spot in which the vines could thrive naturally because farmers didn’t have the resources and infrastructure to irrigate, fertilize, and use bottled solutions.

Starting in the 1950’s, the American wine industry fetishized and then capitalized upon and commoditized specific grape varieties to such an extent that varietal labeling became codified in labeling laws and embedded in our vineyards, literally. Industrialization had facilitated the clearing of forests, draining of wetlands, and planting of mass monocultures. We began planting single varieties of French grapes that came into vogue after WWII because of the fond memories of GI’s returning home from their service in Europe.

Now entire regions (like Napa), and even entire states (like Oregon), are known for monocultures of one or two varieties of grapes. This has been seen as a good thing – a “handle” for the consumer that allows for ease of marketing.

We have built “brands” of grape varieties. Most Americans will order a glass of Cabernet or Chardonnay without any concern for its provenance. “I’ll have the Cabernet.”

Enter climate change.

While our investments in single varieties of grapes has not changed, those grapes’ ability to be grown well or even survive is being tested by rapidly changing environmental factors. Generations of cloning the same vines has arrested the development of better adapted varieties.

The result is that regions built on monocultures take ever more and more extreme measures to attempt to ensure that their all-in bet on Pinot Noir, for example, does not turn out to be like putting all your chips on a single number on the roulette wheel, i.e. a sucker bet.

If a wine is branded by grape… what do you do when that grape no longer thrives?

The answer, sadly, is that you constantly replant new vineyards to replace prematurely decrepit vines and clear and exploit new regions where that grape might thrive. Meanwhile you must spray enormous amounts of chemicals, and expend exorbitant amounts of resources providing things like shade and water, to give life support to the grape where it currently grows.

Growers of high-end Cabernet in Napa install shade cloth to shield entire vineyards of grapes from the intensity of the sun on the southern and western sides of the rows. These same vineyards, planted on the hot, dry hillsides of the Napa Valley, must irrigate constantly with rapidly disappearing ground water. These are just a couple examples of the actions considered de rigueur to support a single variety of grape originally adapted to river banks in a much cooler and wetter climate.

Even if we see the writing on the wall for this kind of behavior and recognize its folly, because of our varietal obsession we will likely propose the wrong solution.

Our varietal obsession threatens to cause us to just seek the next newer and better variety of grape, rather than see that we need to think of wine as a process.

Change is inevitable and constant. So even if we were able to breed a new grape that was resistant to every known virus and mildew without spraying, and tasted exactly like Cab Sauv even with 3 months of 110 degree heat and 5 inches of winter rain, it would only be a matter of time until a new environmental condition occurred that it wasn’t bred to handle.

The point is that we need to stop searching for the Holy Grail of wine grapes and recognize that a thriving wine culture is a process of continual adaptation… it is a Quest that never ends.

Once we realize that the end is adaptability, not a newer better grape variety, we can begin to see the wisdom in branding things that can function as containers for constant change and adaptation.

Grape varieties cannot be these containers for change, because we may need to change the variety of grapes we use in order to incorporate newer, better adapted varieties. So this is why I’ve stopped labeling Centralas wines with grape varieties.

What kind of container for change should we use?

Location is an old one, and a good one.

For example, people generally don’t care that their Champagne is a blend of up to 6 grapes, or that Champagne (the region) recently changed their laws to allow a newer, better adapted variety of hybrid grape, named Voltis, to be used in the blend. Similarly, does anyone care that their bottle of Bordeaux may now contain 6 new hybrid varieties of grapes?

All of the new grapes approved in these locations were specifically chosen for their potential to flourish even in the less hospitable conditions caused by global warming. This is a triumph for regional, rather than varietal, branding.

However, there are some potential drawbacks to location branding. If a region were to become known for lower quality, it may hurt those who were standout producers. Another disadvantage is that a location brand doesn’t allow for the rugged individualism that we Americans prize so highly. What if I want to make a sparkling rosé in a region known for rich reds?

There doesn’t seem to be an obvious, one-size-fits-all solution to how to proceed once we release our attachment to grape varieties. Likely a hybrid of producer and location branding, with some exceptions, will be necessary.

But to me what is obvious is that to save wine we need to let go of our obsession with specific grapes, and maybe even with grapes in general, and embrace wine as a living process.

The Ecology of Wine

We recently got invited to pour Centralas wines for a party hosted by an ecologically focused landscape design company here in Los Angeles named Viola Gardens. As an ecological winery, we thought it would be a great fit.

And it was. My talk garnered applause, and even some cheers. I talked about the ways we attempt to protect or benefit the environment and our community with every decision we make for Centralas, how we want our wines to showcase the unique flavors of our local region, how the wisdom of vines can help extricate us from our cultural climate crisis, and how we see ourselves as merely helping vines lure people in with booze and then re-connecting them to the earth.

Then came Andy the ecologist.

Native grapes building relationships.

Ecology, maybe I should mention, is the biological exploration and understanding of the relationships of organisms to one another and to their environment. As evening settled into a lush hollow in Topanga Canyon, Andy stood before us and immediately connected us to the relationships going on around us.

“Close your eyes and listen. What do you hear?”

He began identifying the songs of the White-Breasted Nuthatch, the Yellow-Throated Warbler, the Canyon Wren, and more – calling them out as they sang in overlapping choruses – and it was as if the forest suddenly became three-dimensional.

Why hadn’t we heard these songs before? Moments before they had been a sort of background white noise for our self-absorption. But now we not only heard birdsong, we heard individual voices.

Andy went on to explain that by paying attention to the song of the birds, we could know that nearby there would be certain kinds of trees and shrubs, or that there would be water nearby, because each type of bird had individual preferences for the kinds of habitat they like to live in, and the kinds of things they like to eat.

Birds, as Andy further elucidated, were singing about all kinds of important things. Not only the presence of food or water, but also of predators and prey, and the activities of all kinds of forest creatures whom they could see from their unique vantage points.

With eyes closed we began to see in all directions, deep into the woods. We became aware of how the songs of birds could be the keys to unlock the secrets of an entire ecosystem.

With rapidly dawning awareness we experienced one of those rare moments, in adulthood, of real wonder.

Andy had us open our eyes then, and concluded his mind-altering talk by saying something like this (paraphrased):

The birdsongs you hear are a form of energy. The energy of the sun and earth, balanced in this just-so cosmic cycle, grows into trees and plants. That energy is eaten by insects, which are then eaten by birds, who use that energy to sing. So when you hear a birdsong, you are hearing an expression of a diverse ecosystem which is bathed in the energy of the universe and translated through innumerable deaths and lives.

We all sat silent for a moment as he finished. In the silence, we heard the singing of the birds more clearly than ever before.

I couldn’t help but think of wine, of course, and Maya’s speech* from the movie Sideways about why wine moves her:

“…I like to think about the life of wine…How it’s a living thing. I like to think about what was going on the year the grapes were growing; how the sun was shining; if it rained. I like to think about all the people who tended and picked the grapes. And if it’s an old wine, how many of them must be dead by now.”

Wine is also a translation of cosmic energy through its relationships. “Transubstantiation” may be a more appropriate word.

Like birdsong, wine has an ecology that involves trillions of soil microbes and air and sunlight. But while we can imagine removing humans from the birds’ ecosystem without ill effects (and maybe with some beneficial effects at this point), we cannot remove wine from its relationship with humans.

Wine depends on relationships to both human and extra-human culture. It sings of the inextricable relationship between humans and the earth and the universe.

Each bottle of wine, just like a birdsong or any song, is a little cycle of life and death. The silence between each note and phrase gives beauty and meaning to them. The pause between each sip allows us to savor.

Perhaps we love to open and drink bottles of wine for the same reason we love to listen to songs. Each bottle of wine we open, and savor, and finish is like the beginning, middle, and end of a song, which echoes the cycle of our own life.

Both are cycles that we repeat, again and again - being moved, learning how to better appreciate their meaning – simultaneously rehearsals and coping mechanisms for our mortality.

“And,” to quote Maya* from Sideways again, “…it tastes so f***ing good.”

Veraison begins at Crenshaw Cru.

Cheers,

Adam

*I'm actually not quoting Maya. Maya was a fictional character played by Virginia Madsen. But I'm not quoting Virginia Madsen either. She's an actor who was just saying her lines well. Her lines were written by Alexander Payne & Jim Taylor. Am I quoting them? Maybe, maybe not... because Sideways the movie was based on Sideways the novel written by Rex Pickett... and I haven't read the novel. As a former Writers Guild Foundation employee (Wendy and I met in the library), I am compelled by law (the ironically unwritten law of the Writer's Code) to give appropriate credit for movie quotes.

Progress Report - July 2022

There is actually some good news out there, and we've decided to start sharing some of it on a regular basis. We will call it a "Progress Report" because we think these are hopeful stories of things moving in a positive direction.

If you want the "Regress Report" you can go to your preferred news channel, but we hope this series will offer a reminder that the "news" doesn't give you the whole picture.

The other good news is that we're only telling the positive stories that relate to wine. Imagine how much good news there must be that isn't related to wine!

Progress Report - July 2022

9th Circuit Court Orders EPA To Re-evaluate Glyphosate… and Do It Right This Time

http://winecountrygeographic.blogspot.com/2022/06/environmentalists-win-major-court.html

What's good about this?

Glyphosate is the most used herbicide on the planet. The rise of GMOs is directly tied to the desire to broadcast glyphosate over massive corn, soy, and wheat fields to kill weeds without killing the crops. What that means is that if you eat any product that is not certified organic (cereals, crackers, cookies, breads, pastas, chips, etc... and wine) you are eating a food that was most likely saturated with glyphosate. It is used so widely and indiscriminately that it is found even in organic foods from farms that haven't been sprayed with it for decades. There have been studies for decades showing that glyphosate is insidiously harmful to human health, but because of the lobbying of Big Ag, the EPA has not restricted the use of glyphosate in our food system. There is evidence that this has been for very greedy reasons. Finally, the EPA is being forced to reconsider the facts. Learn more about glyphosate in wine here.

Slow Food Introduces “Snail of Approval” – An Ecological Approach to Greatness in Food & Beverage

(This may remind you of the Ecological Wine Score)

https://slowfoodusa.org/snail-of-approval/

What's good about this?

For far too long, the evaluation of greatness in wine has been disconnected from any context related to its growth and production. We desperately need to start evaluating more than just the taste of wine. How it's grown, who grows it and produces it and how they are treated and compensated, land stewardship, and community impact are just some of the very important aspects of greatness in wine that are regularly ignored by nearly every wine reviewer. Slow Food's "Snail of Approval" is the most comprehensive inclusion of the context of wine in wine evaluation that we've seen (next to the Ecological Wine Score), and deserves a round of applause, if not a standing ovation.

What If We Prioritized “Gross National Happiness” over Gross Domestic Product?

https://www.cnn.com/2019/09/13/health/bhutan-gross-national-happiness-wellness/index.html

What's good about this?

Bhutan may be the most inspirational country on the planet because of its holistic approach to thinking about national priorities. Rather than prioritizing material wealth as a measure of success, they have decided to measure happiness. If you aren't familiar with Bhutan's pillars of Gross National Happiness (GNH rather than GDP), they are worth a study. Bhutan has also written into their constitution a limit of 33% development of their country, with the remaining 67% left as national forest and parks. They are the only carbon negative country in the world, and they have a goal of being the first 100% organic nation within this decade.

Special recommendation:

Adam recently interviewed the guy who is planting the first vineyards and developing the wine industry in Bhutan for the first time ever in its history. Check out this fun interview on the Organic Wine Podcast.

We hope you enjoyed some positive and inspirational news for a change. That strange sensation you may be feeling is just hope. Perhaps you haven't felt it in while, but don't worry... studies have shown that it can be beneficial to your mental health.

Speaking of progress... that little lady in the Crenshaw Cru vineyard with Wendy (on the CentralasWine.com homepage) recently spent the day with us again at Crenshaw Cru. She's a couple years older now, but just as adorable (see below). She - and every other child who will inherit the world we leave behind - is one of our inspirations for doing the work that we do.

Cheers!

Adam & Wendy

Why does Centralas’s HELLO, OLD FRIEND white wine taste the way it does?

Our 2021 white wine is made from the grape Fiano, grown in a vineyard that was farmed organically in Hemet, California. These facts create some of the most dominant flavors of the wine.

Fiano is a white grape (really a yellow/green grape) whose home in the Old World is Campania, Italy. It is a grape that was probably selected over the centuries to be grown there because, in addition to complex and perfume-like aromas, it retains its acidity and freshness even in the heat of Southern Italy.

I know this is why the owner of Tranquil Heart Vineyard chose to grow it in Hemet, whose heat makes Italy’s heat feel refreshing. I mean it gets really hot in Hemet. Because of this intense heat, I chose to pick the grapes on the early side, aiming for 20-22 brix, despite their natural ability to retain acidity, because, as a general rule, as grapes ripen they increase in sugar content (brix) while they diminish in acidity.

The grapes came in at approximately 20 brix and 3.3 pH, pretty close to what I wanted.

When I say “came in,” what I mean is that I picked up a ton of grapes in Hemet, drove them to our production facility in Moorpark, crushed them and siphoned the juice to tank to settle. After settling approximately 24 hours, we measured the brix and pH, then siphoned the clear juice off the sediment to two neutral barrels (and a carboy or two).

I was mildly disappointed that the brix were so low, fearing that the grapes hadn’t achieved full flavor development before picking. Tasting the finished wine now, I’m really glad they were what they were. Any more ripeness would have led to a very big and flabby white.

Once the wine was in barrel, I just allowed the wine to do its thang. That’s technical speak for, “I did nothing.” Natural yeasts on the grapes or ambient in the winery completed the fermentation.

Doing nothing actually has several consequences to the flavor of the finished wine. First of all, when you don’t add yeast, multiple strains of “wild” yeast and bacteria begin the fermentation, adding their own unique characteristics until the next dominant strain that can withstand higher alcohol and higher temperatures take over the fermentation, until finally the big guns – Saccharomyces cerevisiae – take over and finish the alcoholic fermentation.

This ecological succession on a micro-biological scale creates complexity in the aromas and textures of a finished wine.

Fiano is already know to have varietal characteristics of honeydew, hazelnut, Asian pear, orange peel, and pine. But a wild fermentation can add to this many tertiary flavors.

There is one aroma and texture you may pick up on HELLO, OLD FRIEND that is not from fermentation… or at least not from what is known as primary fermentation (the conversion of sugar to alcohol and CO2). That flavor is what you may sense as buttery-ness, buttered popcorn, butter fried nuts and a creamy texture.

Butter in wine, like in a big buttery Chardonnay, comes from a secondary fermentation, a process known as malo-lactic fermentation (MLF).

When tart fresh grapes come into the winery they contain malic acid. Malic acid in wine is unstable, because the grapes also come in with lactic acid bacteria (LAB) which eat the malic acid and convert it to lactic acid and CO2. The most common LAB in wine is Oenococcus oeni.

Malic acid – from malus or apple – is the sharper acidity you taste when you bite into a green apple. Lactic acid – from its association with milk – lends a softer, creamier texture to the wine.

If you do nothing, as we do, the natural LABs will naturally convert the sharper malic acid in the wine into the creamy lactic acid, and will also produce a compound called diacetyl. Diacetyl is the compound responsible for the buttery flavors and aromas in, especially, white wines like Chardonnay and Fiano.

Now not all natural process are equal, as different strains of LABs under different conditions may produce more or less diacetyl. Thus there can be variation in the amount of buttery-ness from year to year in a white wine even when it is made from the same grapes and in the same way.

The only way to prevent MLF is to intervene in some pretty extreme ways. You have to add extra sulfites, chill the wine, and then sterile filter it. This first prevents the process from starting, and then removes the LABs that would cause it to happen.

You can also inoculate the wine with a cultured strain of LAB known to produce low levels of diacetyl. This would stabilize the wine while giving you a low level of buttery-ness, but again is a level of manipulation I find unnecessary. And I very much enjoy the level that occurred naturally in HELLO, OLD FRIEND.

This whole concern about MLF is because you don’t want it to happen after you’ve bottled the wine. You want to ensure complete MLF has happened in the winery, or you want to take the necessary steps to prevent it from ever happening, because if it happens after bottling, you’ll end up with an unintentionally spritzy wine – as the CO2 produced by MLF is trapped in the bottle and absorbed into the wine – and often some strange aromas that would have blown off if MLF happened outside of a bottle. Also the pressure from that CO2 production in bottle might push the corks out partially.*

New oak barrels are often thought to cause the buttery-ness you taste in wines like Chardonnay, but now you know the real reason: diacetyl from MLF.

New oak barrels do contribute a richness and concentration, and sometimes a softer, arguably creamier, texture. But the aroma/flavor profile of new oak in white wines is more along the lines of vanilla, toasted coconut, caramel and/or butterscotch, and even a maple-bacon smokiness. (Given this list of flavors, in addition to buttery-ness, I don’t know why an oaked chardonnay isn’t a more common breakfast item.)

Regardless, even if new oak could contribute to the buttery aromas/flavors you may detect on HELLO, OLD FRIEND, I didn’t use any. I only used barrels that had been used enough times to impart no flavors (though they still contributed to the texture of the wine).

Now, going back to the brix level. At 20 brix, the wine I made previously from grapes from Santa Barbara County would end up with less than 12% alcohol. So I was caught off guard when HELLO, OLD FRIEND finished at over 13% alcohol. The alcohol conversion rate went from a factor of .59 to a factor of .66 in our new facility with non-Santa Barbara grapes, and I honestly don’t know why that is. I do know that we’d have to get into some serious chemistry to begin to understand it. And I do know that the extra alcohol changes how the wine tastes.

A final technical factor that impacts the flavor of this wine is the fact that even though the wine went “dry” – as in the yeast ate all the available sugar and died off naturally when there was no sugar left to eat – there is still over 2 grams of residual sugars (RS) in the finished, dry wine. This could be a combination of tiny amounts of sugars the yeast couldn’t ferment like cellobiose, galactose, and pentoses, or it could just be left-over fructose or glucose. The point is that while 2.2 grams of RS won’t make the wine taste sweet, or even off-dry, it will be noticeable in the overall impression of the wine’s flavor… I think to its benefit because it balances the acid in the wine and adds a little “fat” to an otherwise lean wine.

So there you have it. Please let me know if you have any questions or comments!

Cheers,

Adam

*(Of course I had to put in a footnote.) If you drink a lot of natural wines, you may have a higher than average chance of encountering this phenomenon of unintentionally spritzy wines. If so, you can either drink it as is – some wines benefit from accidental MLF in bottle – or you could decant it for a couple hours to allow it to go “flat.” Or, using an ancient sommelier’s secret, you could pour the wine into a blender and turn it on for 30 seconds then pour it back into the bottle or a decanter – instant decant.

Of Vines & Dolphins

There’s a true story about a dolphin named Ruby that gives me chills every time I remember it. It’s from an out of print book called Mind In the Waters. (Bear with me. I swear this relates to wine.)

A scientist, who was studying dolphins, got to work with Ruby. They developed a friendship, and one day the scientist decided to try to teach Ruby to say her name… as in pronounce it as a human would in English.

He called Ruby to the edge of her pool, and began, using verbal explanations and toy-based motivational techniques, to attempt to get her to imitate the sound of her name.

Once she understood the game, in less than ten minutes Ruby transcended dolphinese and pronounced something that was so close to the human English version of her name that it was eerie.

Dawn breaks over Crenshaw Cru.

But then she just as quickly stopped pronouncing her name and would revert back to dophinese. She didn’t seem capable of repeating her name whenever he asked her to. She would say her name, and then go back to repeating other sounds, shaking her head, presumably not understanding the scientist’s intent.

She seemed to be as frustrated by the process as the scientist was. At times she would swim all the way to the other side of the pool and back when he would begin the lesson over. He tried repeatedly to get her to consistently show that she could pronounce “Ruby,” but she eventually stopped and seemed set on speaking dolphinese.

Finally, nearing the end of his time and energy to stay with her, something clicked. The scientist noticed that Ruby was repeating a particular set of sounds in dolphinese, so he tried repeating them back to her. She would repeat them again and he would listen closely and try to more accurately imitate her.

Suddenly, something caught the scientist’s ear, and he realized that what she chittered back to him were the same sounds she’d been repeating since he began his “lesson.”

He was stunned to understand that while she had learned how to say her name hours ago, he was just now learning to say the name that she had given to him.

Amazingly, at the moment of dawning awareness for the scientist, Ruby saw the lights go on in his eyes, and she exploded in frenzy of glee and excitement.

Finally, after hours of training, her student had learned his first word in dolphinese.

It can be humbling to the point of humiliation to admit how highly we have thought of ourselves, and how wrong we were about something. I try to laugh at myself. It’s either that or weep, and laughing seems to give me the energy to get up and try to do better, to listen better, to engage in the process of growth… again.

Growth, I think, is a process of learning how much I have to learn… and unlearn.

For example, as a gardener and farmer, for years I envisioned my relationship with land and plants as one in which I was in charge. I was the Director of Vineyard Operations. Ego > Earth.

I’ve come to realize that with that perspective my viticulture can only be so-so.

That perspective is like giving your 8-year-old the keys to your new Maserati and expecting them to get themselves to and from elementary school. They might actually do it, eventually, but your Maserati won’t be new anymore.

In terms of life on earth, humans are approximately 8-year-olds (no offense intended to 8-year-olds). Grapevines, and most plant life, have been around much much longer than we have. Each plant embodies millions of years of wisdom.

Seen in this perspective, I’ve begun to realize that my role as a gardener and farmer is that of a somewhat illiterate student. Plants are my teachers, and I’m learning to listen to and observe their lessons better. I’m learning to respect the eons of knowledge they animate.

For plants and dolphins, the herculean task of getting us humans to listen and then learn something from them is a task their life depends upon… which may be why they seem to have infinite patience for our dullness.

What’s great about wine is that it gives us humans a reward for listening and learning to be better servants and stewards of the earth. Wine actually tastes better the more literate we become in the language of vines and ecosystems.

Maybe that’s why the vines offer it up. Maybe it’s the carrot they use to motivate their students to want to learn and grow.

As I recall tasting our Crenshaw Cru red wine during bottling recently, and how thrilled I was to discover how good it tasted, I can’t help but imagine the vines waving their shoots in the air, even more excited than me that I had finally begun to hear what they’d been saying to me for years.

Do Nothing To Save The World

Paying attention is exhausting. If you follow the news, read books and scientific studies, listen to podcasts, and generally look out your window, it’s hard not to feel overwhelmed, saddened, outraged, and helpless.

Some of this is intentional. Distracted, helpless-feeling people become indifferent. Caring takes too much energy. When we switch off to preserve what little energy and sanity we have left, it allows those with power to do whatever they want with much less resistance.

This becomes a vicious cycle. The actions of the powerful (and any human, really) as a rule are motivated by self-interest rather than altruism, so the results of those actions usually make the world a worse place for the majority of us. That gives us more reason for outrage and sadness… which, when added to an already full slate of disasters, ironically gives us more reason to shut ourselves down as we feel spiritual fatigue and distraction paralysis from being inundated by negativity.

I feel fatigue just writing about this, so I’m guessing you feel the same reading it.

But wait… there’s some really good news!

Some of the most important things you can do to benefit the environment, as well as your own health and the health of everyone on earth, require that you do LESS.

That’s right, you can actually help the environment by eliminating things from your to-do list and building your stores of personal energy.

Saving the world can leave you feeling refreshed and rejuvenated!

As it turns out, many of the issues we face in the 21st century result from a culture of constantly wanting more. We have sped up nearly every aspect of our culture because of this. We eat, read, drive, and work faster than we ever have in history. We also sleep less than we ever have.

Yet our health and our life spans are declining, evidence that the faster the rats run the sooner the race is over. Maybe we should consider slowing down.

Here are ways that you can expend less energy, even increase your energy, while solving some of the world’s biggest problems:

1. Sleep more.

When you sleep, you aren’t driving, eating, working, consuming media or in many other ways consuming resources and releasing carbon into the atmosphere. When you sleep you are healing your body and mind.

There are some interesting statistics about sleep. First, there is a huge correlation between less sleep and health issues and shortened lives. Secondly, corporations have done some studies and found that lack of sleep is costing business hundreds of millions, even billions, of dollars annually in lost productivity.

On the flip side, there’s a statistic that if Americans all increased their nightly sleep time by 1 hour, the economy would implode. In other words, we’ve grown our system to be dependent on consumption to the detriment of health and well-being.

So… sleep more and defund industrial capitalism.

Maybe we don’t want the economy to implode. But maybe we want to send a message that it’s time for a change. How about 45 minutes extra sleep each day? That’s a nice after-lunch nap.

Siesta anyone?

2. Stop taking care of 10% of your yard.

I know not everyone has a yard, but if you do you have an enormous potential to benefit the environment by selecting a section of your yard and… doing nothing to it.

Don’t mow it. Don’t water it. Don’t fertilize it. Don’t spend an ounce of extra energy or resources on it.

Then see what happens.

The grass will grow, seed, and die. Eventually weeds will grow. Then small shrubs. Someday a tree or two may grow. If you’re in an arid climate you may not get beyond the weed stage in your lifetime. But that’s okay.

Throughout this process of ecological succession, that part of your yard will be sucking carbon out of the atmosphere and sequestering it in the soil. It will provide habitat for insects and small creatures. It will quickly increase to have much more biodiversity than it had as a lawn. It will be a literal nature preserve that you accomplished by doing nothing.

3. Focus your consumption on quality over quantity.

Do you fantasize about that special bottle of wine? That organic, pastured beef filet? Those succulent and colorful but pricey farmers market local organic veggies? But never buy them because you think, “I could get 5 normal grocery store versions of that for the same price.”

Well, go ahead and buy them… but don’t change your food budget.

The quality of the food you eat and wine you drink will immediately increase, while the quantity decreases. That means you may lose weight and enjoy what you eat and drink more. To me that sounds great.

You can apply this thinking to media as well. To driving. To flights. To work opportunities.

Learning to say “no” to the OK or even the Good, and “yes” to only the Best, reduces the amount of energy and time you use on lower quality experiences. Reducing quantity gives you more resources for quality. Less really is more.

When you consume less, you can consume more thoughtfully. You can take the time to get to know the people and stories behind the products. You can reconnect your life to the context and culture that you fund with your consumption choices. You have more time to be thoughtful about the kind of world you are creating.

2021 IF YOU’RE FALLING

Grapes: Muscat and Viognier from and uncultivated vineyard in the Antelope Valley of Los Angeles County.

Prickly Pears: foraged from an uncultivated space in South Los Angeles, and picked from an uncultivated orchard that is the only one of its kind atop cliffs over the Pacific Ocean in Los Angeles.

Ingredients added during winemaking: grapes, prickly pears, tartaric acid, sulfites.

Grapes and prickly pears were picked at different times and fermented separately, indigenous fermentation, then combined in barrel. Because of the chemistry of the prickly pears (pH 5.35) tartaric was added to prevent spoilage. Settled in neutral barrel for about 6 months.

Picking prickly pears is difficult and, at times, painful. Working with them in the winery has unique considerations. How to handle the needles? How to deal with the low acidity? The fermented juice of the prickly pears is so viscous that it is more like a gel, so diluting it in a tart wine seems an ideal way to solve multiple challenges. The resulting wine has more viscosity than a typical wine, and it is cloudy. The taste is unique… hibiscus, peach blossoms, and palo santo come to mind but don’t quite capture it.

California, and the entire Western United States, is in the midst of a mega-drought. And it could get worse.

As an ecological winery, we believe that we should be using locally indigenous fruits that don’t require irrigation. We may live to see a time when water is diverted away from things like vineyards in order to allow for human survival. Prickly pears are indigenous to Los Angeles and thrive only on the winter rains, even when they are minimal, even in marginal land. They show us a way forward in harmony with our land.

And there is a story implicit in the very existence of this wine. White European grapes, brought originally to Los Angeles by European colonizers, are blended with colorful indigenous cacti. The wine is a reflection of the complex and troubling history that has shaped the current culture of this land. But it goes even deeper into the personal histories of the folks who grew the grapes and the cacti. It’s too long of a story to tell here, but we hope this wine inspires you to reflect on the history of your land… wherever you are.

John Ildefonso, the artist of the watercolor on the label, is a Los Angeles native whose own story enables him to capture the essence of this wine. We first saw John’s work on exhibit at the Mexican Consulate here in Los Angeles. Later we saw a series of paintings he made to bring attention to the history of racial class structure in Mexico, in which he used images of prickly pears. When we began to conceive of IF YOU’RE FALLING, we knew we had to ask John for his input on the label. We are extremely grateful for his generous gift of this painting. It says much more than we could, and we think it elevates this wine to something more than just a commodity.

Quite frankly, we love this wine. For what it is and for what it stands for. It is unique, and uniquely from our home terroir.

The name “If You’re Falling” comes from the sentiment, “If You’re Falling, Dive.” To us this means that we can still find a way to craft beauty out of bad circumstances. We can be the band that played as the Titanic sank. We can share grace on our way down. It also means to not fight it, to embrace it, to fully commit. Like if you’re falling in love… dive in head first. Many things are out of our control, but our response to them can still reflect the best that we are capable of.

2019 RED HOT WINE

Vineyards: Pinot Noir grapes came from two vineyards, both certified Organic. One in the Santa Rita Hills AVA, and the other on the ocean-side of the boundary and just outside of Santa Rita Hills. Santa Barbara County.

Viticulture: Certified Organic, one vineyard is no-till & also certified biodynamic. Hand tended & picked.

Ingredients added during winemaking: grapes, water, tartaric acid, sulfites.

Destemmed, acidulated water added to balance overly ripe grapes from one vineyard, indigenous fermentation, aged in 1 new French oak barrel and 2 neutral barrels. Bottled unfined and unfiltered after a year. Aged in bottle for an additional 2 years before release in 2022.

We didn’t think we could make a certified organic Santa Rita Hills Pinot Noir for under $30. It took us 3 years to figure out how. Okay, we fudged a little on the boundary of the AVA and it isn’t all technically from Santa Rita Hills. But it sure tastes like it.

We think farmers are hot. We think good farming is hot. And by hot we mean super attractive, desirable, and sexy.

We want more good farming and hope this wine inspires you to want it too.

The "Pollock-esque" label was painted by our neighbor and friend, Presley Burroughs. Presley and his wife Faith welcomed us to their neighborhood with a bottle of wine when we move here 10 years ago, and we are delighted to honor that ongoing friendship by featuring Presley's painting on this little something we call "RED HOT WINE."

Presley titled his painting “20 +/-”

2021 Hello, Old Friend

Vineyard: Tranquil Heart, Hemet, CA, Riverside County. Fiano block.

Viticulture: no till, no herbicides, no synthetic pesticides, hand tended & picked, bee friendly

Ingredients added during winemaking: grapes, sulfites

Whole cluster pressed, indigenous fermentation, settled in neutral barrels for about 6 months before bottling. No fining, no filtration.

The first white wine made by Centralas has a label that features the earth greeting us as an old friend. There can be so much emphasis on the harm that humans have wreaked on the world that we lose sight of the truth that we are not adversaries.

The old idea of "Human versus Nature" is founded on a dichotomy that doesn't exist. We are nature too. For millennia we lived in harmony with the earth and her rhythms, as part of them, enhancing the health and vitality of the world. It has only been in the last 100-150 years or so - really a blip in time - that some of us seem to have lost that connection.

While we may have been estranged from our friend, she hasn't forgotten. She's reaching out with a reminder that what we share runs deeper than any temporary issues. She's our soil mate... our Ride or Die.

Crenshaw Cru 2021 Sparkling Rosé

Vineyard: Crenshaw Cru Winegarden – entirely from the front yard block. 1 meter x 1 meter spacing, Riparia Glorie rootstock, Syrah Tablas Creek Clone, 14 vines

Viticulture: no till, deficit irrigated (watered 4 times during the growing season), hand tended & picked

2020-21 Vineyard inputs: water, compost, compost teas, cover crop seeds, Stylet Oil, sulfur, Cinnnerate

First pick: 8/22/21, 19.5-20 brix, 3.25 pH

Second pick (smaller amount): 9/19/21, 22 brix, 3.4 pH

Wendy foot tread and immediately pressed

Ingredients added: grapes, yeast, sugar (as tirage for in-bottle fermentation)

Disgorged: 4/24/22

Class: Brut

We tend Crenshaw Cru as an exhibition of the magic and vitality possible by combining ancient agricultural perspectives with modern viticulture techniques in an urban/suburban setting. Crenshaw Cru is a micro-ecosystem meant to show the potential for the macro-ecosystem. The wines that we make from it are unique in the world.

The 2021 Crenshaw Cru Sparkling Rosé is the first Crenshaw Cru wine to be made by Centralas, and it’s the first commercial wine to be produced from grapes grown in South Los Angeles. It was released only to the Centralas Wine Club.

We made this wine in the traditional method by fermenting the pink wine dry, then bottling with some sugar to restart a second fermentation in the bottle. After this fermentation was complete, we allowed the lees to stay in the bottle for about 6 months, riddled, then disgorged. We used more of the same wine as dosage. The wine is now coppery in color, with rich and complex flavors and textures, and a mouth-watering finish.

Greg La Follette - From Soil To Bottle

This is where you can view or download Greg La Follette’s “From Soil to Bottle” presentation as a pdf. He referenced this in his Organic Wine Podcast episode.

Organic Wine Podcast Episode 69: Aaron Brown and Colin Blackshear of Bardos Cider

Bardos makes cider from fruit gleaned from hundred year old abandoned orchards in Northern California.

Episode 69 of the Organic Wine Podcast