Promiscuous Viticulture: Crenshaw Cru Polyculture Winegarden Provides Inspiration

Crenshaw Cru – our estate polyculture winegarden in South LA - was born of necessity. I had to squeeze a very big love of growing things into a much too small urban yard.

I tried to overcome this discrepancy with dense, overlapping plantings. “Greedy for Green” might have been a good slogan for my approach to planting Crenshaw Cru in the beginning.

Ten years later, I’m realizing I may have stumbled on a form of vineyard polyculture that could provide vital resilience, and improved wine quality, in the face of climate change.

Tree Trellis. Credit

The Context of Promiscuous Viticulture

If you haven’t heard the term “agroecology” then you probably don’t listen to as many alternative farming podcasts as I do.

The truth is, though, that agroecology – as well as the related terms of agroforestry, silvopasture, alley cropping, and perennial polycultures, food forests, and winegardens (some of which we use to describe Crenshaw Cru) – are more than just trendy words used to describe ancient systems of farming (though they are that too).

All of these words are reactions against, and potential solutions to, the harm caused by industrial monocultures. There is a renaissance of thought happening right now in agriculture, and you will hear these words more and more.

Nature doesn’t do monocultures very often, and when it does they are usually temporary phases that serve as transitions after traumatic occurrences like fires, floods, landslides… or human folly.

Diversity is nature’s way of building adaptability and resilience – the ability to survive anything – into an ecosystem.

So when you remove diversity from an ecosystem and segregate 20 or more acres of one thing – like grapevines – you inevitably end up with a less adaptable and less resilient system (and, I would argue, a much less beautiful and enjoyable system as well).

Nature doesn’t have a favorite variety of grape either. Nature continues to select the grape that is best adapted to where its seed falls at that time in history. When historical conditions or the land itself changes, and that grape no longer thrives where it grew, nature grows another, different, better-adapted vine in its place. We can learn from nature by incorporating breeding and selection as an ongoing process in our idea of a vineyard.

All of this, by the way, is yet another reason to end our varietal obsession.

Diverse polyculture viticulture with animal. Credit: Jakob Philip Hackert

Re-Learning Viticulture

I’m in the process of re-thinking viticulture, and I’m inviting you to join me.

“Re-learning” viticulture is actually more accurate, because many of these ideas are the way that vines were grown for thousands of years before the industrial revolution and the conversion to intensive, large-scale, industrial viticulture and agriculture.

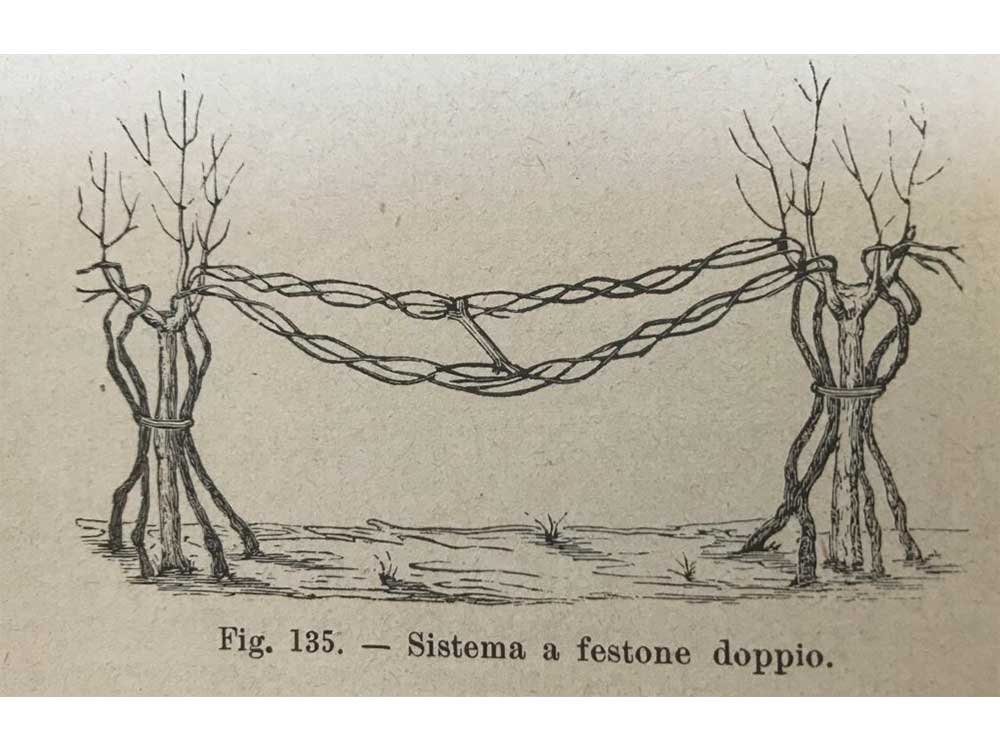

Instead of posts and wires, we used to grow vines on living trellises called “trees.” These living trellises also produced their own crops of nuts, fruit, and wood – depending on the tree – that added an additional crop to your vineyard besides just grapes, and therefore an additional source of sustenance and income.

These systems were often trained high, at average head height or above. This allowed for animals to graze beneath the vine-trees without being able to reach the fruit, and also allowed for the planting of smaller nut and berry shrubs, annual crops, and grains around the base of the vine-trees and in the rows.

Most viticulture around the Mediterranean (and likely globally) was practiced this way for thousands of years… really since grapes began to be cultivated. It has many names: Culture en Hautain, Joualle, Alberata (a shortened version of vite maritata all'albero – the vine married to the tree), and more broadly Cultura Mista or Cultura Promiscua.

This kind of viticulture is both haughty and promiscuous, apparently.

Rough design of Crenshaw Cru. Yellow lines are rows of vines. Green circles are larger trees that provide shade protection.

How Crenshaw Cru Fits In

While I didn’t plan ahead and plant trellis trees when I planted Crenshaw Cru (though I did in the most recent plantings), I did plant trees much closer than would be considered acceptable in a modern vineyard. Now that those trees have matured their shade presents an unexpected advantage.

Since the trees at Crenshaw Cru are all planted on the South and West sides of the yard, they have begun to shade the vines, at least in part, from the hottest sun of the day. As our hot climate heats up even more, this presents a way to modulate and slow the ripening of the grapes so that they ripen more gradually.

The shade of the trees, in other words, can act as a buffer against extreme heat… therefore potentially benefitting grape flavor development and ultimately wine quality.

There was a time in history when we wanted to get as much sun on the grapes as possible to ensure full ripeness. This hasn’t been an issue for a long time in California, and now the opposite is actually true: we want to solve the issue of extreme heat and ensure that ripening doesn’t happen too quickly.

We don’t need to trellis the vines on trees to make this happen. We could simply plant trees strategically throughout existing vineyards. Or if we are planting a new vineyard, we could design it in small plots with lines of tree buffers on the southern and western edges… just like Crenshaw Cru.

Both of these options would integrate trees into our idea of a vineyard while continuing to allow the ease of care for and harvest of the vines that modern vineyards maximize.

There are many other benefits from incorporating trees in and around vines. Trees drop their leaves and needles creating a beneficial, fungal mulch for any vines growing nearby. Trees pull additional nutrients out of the air and put them down in the soil where they provide for both themselves and any nearby vines. Trees can create a more moderate microclimate for the vines, protecting them from extreme winds, hail, and frosts. One experimental vineyard in France has even found, counterintuitively, a decrease in mildew pressure on the vines.

My suggestion for trees to use in California, and similar climates, would include pomegranates, figs, and olives - all of which are very drought tolerate, traditionally used in promiscuous viticulture, and produce their own crops. Also live oaks, ponderosa pines, possibly even sycamores would be equally suitable to our dry climate, and could get much larger and more shady than the fruit trees.

When we plant vines near trees, and vice versa, we’re doing a lot of wonderful things that may help provide solutions to problems that we caused. But ultimately, we’re just finally listening to nature and heeding its example.

Vines evolved to grow on trees. They are symbiotic, not parasitic. They are natural friends.

Maybe it’s time we reunited them. Maybe it’s what they’ve been asking for.

Cheers,

Adam Huss

Wild vine growing symbiotically in a forest ecosystem in North-Eastern United States.