Ideas and resources to help you be a more thoughtful wine consumer, maker, and lover.

2020 SYREN - Organically grown Pinot Noir, Santa Rita Hills, Spear Vineyards

Vineyard: Spear Vineyards, single clone/single block, 667 on 5BB, north east sloping clay dominant hillsides, mostly east-west row orientation.

Viticulture: Certified organic, 3 x 6 spacing, VSP, hand tended and picked.

Ingredients added during winemaking: grapes, sulfites

In 2020 we picked twice for this wine, getting two tons of the grapes just before an extreme heat event, and another single ton two weeks later after the heat. This enabled us to craft a surprising lithe and refreshing warm-climate Pinot Noir even in a very hot vintage. Though this wine has classic Santa Rita Hills smells & flavors (strawberry, black cherry, chaparral), the textures and alcohol skew closer to Oregon.

Both batches of grapes were fully destemmed and allowed to ferment indigenously, with a single punch-down per day in two-ton open-top T-bins. Aged one year in used oak barrels. Bottled unfined & unfiltered. Vegan.

We describe the viticulture practiced at Spear Vineyards as immaculate. On the sorting table, the tight clusters of Pinot Noir are pristine, and always seem to be a much easier sort than many other Pinot vineyards we’ve seen in Santa Rita Hills. With this kind of “no expense spared” winegrowing, we see our job in the winery as merely to not mess it up. We make this wine with as light a touch as possible, so you are tasting the most elegant and seamless expression of this land as possible.

This may be our most age-worth wine to date, and will continue to evolve and develop beautifully for the next 15 years or more.

2019 Syren - Organically grown Pinot Noir, Santa Rita Hills, Spear Vineyards

Organically Grown single block single 667 clone Pinot Noir from the Santa Rita Hills.

There are layers of meaning behind the name "Syren" (as we hope you'll find layers of flavor-meaning when you drink it). We can't tell you about everything Syren means to us - some are too personal - but what we can tell you is this:

It is made from a single Dijon clone 667 of the Pinot Noir grape, grown in a single block, in a singular certified Organic vineyard in the Santa Rita Hills. The first wine whose seductive music lured Adam into the world of wine in general, and Santa Barbara/Santa Rita Hills specifically, was a single block 667 clone Pinot Noir from the Santa Rita Hills that he tasted the year before the movie Sideways hit theaters.

The influence of the sea on the land is the reason the Santa Rita Hills exists. The undulating hills draw the essence of the ocean into the vineyards here, in a valley that is unique in the world. Nowhere else this far south in the Northern hemisphere is there a growing region this cool.

It is a liminal region, a fitting home for Syrens, at the edge of things both seen and unseen. The Pinot Noir grown here devours these elements and - when made carefully, gently, and thoughtfully into wine - it holds depths only equaled by the ocean.

The grapes for Syren were hand-picked in darkness. De-stemmed, and allowed to ferment naturally with ambient/native yeasts and microbes, the grape skins were re-submerged by hand each day during a cool, slow primary fermentation. The black wine that results was pressed into 225 L oak barrels - 100% neutral - for 11 months.

In 2019 in addition to a minimal effective amount of sulfites, we added a very small amount of acidulated water to lower and balance the final alcohol content of the wine.

Hussy

Biodynamically grown, barrel aged, single vineyard rosé from Alisos Canyon, Santa Barbara County

Hussy is America's first Grand Cru Rosé.

While most rosés are made with the grapes that weren't good enough for red wines, Hussy is made with the biodynamically grown Grenache and Syrah grapes that were selected specifically for their quality.

Our last name is Huss, so you could say that Hussy is our namesake wine.

With Hussy we celebrate impudent and brazen people who know what they like and aren't afraid to enjoy themselves. We don't think there's any shame in hedonistic and sensual pleasures. Those aspects of wine are why we fell in love with it in the first place, and we think wine should always retain its luscious sex appeal.

A healthy disrespect for tradition is another trait of Hussies. It's one of the quintessential American values that leads to questioning the status quo, innovation, and discovery.

While everyone else is making young, fresh, and fruity rosés, we decided to treat our rosé like a classic white Burgundy, with a twist. We picked ripe, biodynamically grown Grenache and Syrah. We foot-stomped the Grenache to extract color, then pressed it with the whole, dark clusters of Syrah. We added a touch of sulfites and tartaric acid, then barrel fermented (naturally with native/ambient yeasts) and aged the Hussy in 20% new American oak barrels for 11 months.

Bandolero

Single vineyard, biodynamically grown Mourvèdre from Alisos Canyon

"Bandolero" is an homage to the wine growing region of Bandol, France… with a California accent.

Bandol is what we call France's "other Big B" besides Burgundy and Bordeaux. It is located in Provence on the Mediterranean coast, and it is where Mourvèdre is king.

But since Centralas' Mourvèdre is grown and made in California, where the vines hear much more Spanish than French spoken to them, we wanted its name to be true to its current tierra.

Bandolero means "Outlaw." Adam has been a literal outlaw, and being an outlaw led to his love of wine... but that's a story he'd have to tell you in person.

Outlaws are some of our heroes. People who did what was right, even if it went against the flow or the norms for their times. Sometimes you can become an outlaw just by being born in the wrong place or time. Sometimes you have to be an outlaw to be able to create meaning in the face of a vain and materialistic society. If your culture's highest value is business, sometimes you have to be an outlaw just to be human.

Mourvèdre loves heat and dryness. It is ideally suited to the interior of Santa Barbara County where summer lasts into November, and where the biodynamically-farmed vineyards, from which we source the grapes, thrive. It is a grape well suited to climate change.

We love Mourvèdre's unique ability to make black wines that are deep and dark without being ponderous, that have weight without heaviness, that are both layered and lithe.

In 2019 we intended to make wine from Mourvèdre but were unable to find any available that was organically or biodynamically grown. Finally, we were offered some late-season, certified biodynamically-farmed Mourvèdre. Harvested a month after our other picks of Pinot Noir, Syrah, and Grenache, the Mourvèdre was still not over-ripe. The black grapes were hand-picked, de-stemmed, and allowed to go through fermentation naturally with native/ambient yeasts and microbes. Aged for 18 months in 2 oak barrels - half of that time in 1 new American oak barrel and 1 neutral barrel, and the remainder of the time in all neutral - for a distinctively Californian accent. During winemaking we only added a minimal effective amount of sulfites and tartaric acid to protect the freshness and stability of the wine.

Bandolero technically meets the major requirements of Mourvèdre wines made in Bandol, namely that it spends 18 months in barrel, and a maximum 95% Mourvèdre is used in the finished wine (we blended in 5% Syrah). We've tasted this wine in barrel, and it is exceptional. We think it will appeal especially to those with a love of Napa Cabernet - texturally plush and complex with juicy blue & black fruit, notes of licorice, violets, and truffle, and pronounced sweet oak flavors. Alcohol 13.7% - Less than 50 cases made.

Best Technical Podcasts About Wine - 2020

As a winemaker and wine lover, I'm constantly looking for insights and inspiration about growing wine, making wine, trends in wine, and wine business strategies. I also want to get to know the people behind the wine, to learn about new brands, and continue to discover and learn about every aspect of the world of wine.

So the podcasts listed here represent what I have found to be the best options to find all of these things. These tend to be highly technical, and dig into the specifics of viticultural approaches, winemaking techniques, wine business operations, and the nuances of wine region, wine style, and wine personalities.

In short, these wine podcasts are not for beginners or casual wine drinkers. These are the best wine podcasts for wine professionals and wine lovers with advanced wine knowledge or a desire to acquire advanced wine knowledge. These are longform wine podcasts that will fascinate wine professionals and deliver an immense amount of information about all aspects of wine.

I've listed these in two tiers: Consistently Satisfying Wine Podcasts and Often Very Good Wine Podcasts.

Basically every episode of the Consistently Satisfying Wine Podcasts gives me some or all of what I want, and I learn something new from each episode. Sometimes an episode in this category can be so densely packed with info that it bears re-listening.

Many episodes of the Often Very Good Wine Podcasts deliver the goods. When they don't, it's not because they are bad or uninteresting, they just may cover other subjects besides wine (in the case of Consumed or GuildSomm), or delve so deeply (in the case of I'll Drink To That) into wine people that they become almost academic in their personal and regional histories, and lack immediate relevance to someone who is trying to start and run a wine business today in California.

Every podcast on both lists is praiseworthy and deserves a good listen.

Here are the Best Technical Podcasts About Wine in the year 2020:

Consistently Satisfying Wine Podcasts

Chappy Cottrell, the host of Cru Podcast, is also the Wine Director at Barndiva in Sonoma. Chappy does a great job of making Cru podcast high quality and full of well-chosen and highly regarded guests. He delves into many aspects of the wine business, and often elicits great insights into current trends in wine.

I'd love to hear more digging into the technical aspects of winemaking, but Chappy isn't a winemaker, yet, so I'm not really expecting him to go there. Chappy wants his own wine business someday, so we benefit from his desire to learn and make valuable connections.

Cru is a weekly podcast, which is something I love. So many podcasts are sporadic, and I find myself jonesing for another long before one gets released. With Cru, I know there will be a new podcast every Monday.

Some fun notes about Cru Podcast:

- Almost every episode Chappy gives a lengthy introduction that he ends with "without further ado..."

- He asks each guest, "Why wine?" I find it to be a perfect, simple question that immediately gets the guests thinking at a deeper level and sets a thoughtful and more personal tone for the interview.

- At some point well into the interview, Chappy almost always says, "I want to be conscious our your time..." and then he often goes on to ask quite a few additional questions that can take a significant amount of time.

- If your hands aren't free to stop the podcast at the end, you'll discover that Chappy sometimes lets his theme music play for several minutes. It's happy, house-y, dance-y music, and you can transition from listening to a great wine podcast to bouncing a solo dance party in your car (or wherever).

The host of the Inside Winemaking podcast is Jim Duane. Jim is the winemaker for Seavey Vineyard and has some serious Napa Cab cred. Jim is a graduate of the UC Davis wine program (but he probably would not recommend the same path to others... and don't get him started on hipsters). His promotion of self-learned expertise is part of his charm, and clearly a big part of why he started the Inside Winemaking podcast.

Inside Winemaking episodes are released sporadically. Jim is a busy guy, and winemaking doesn't often allow for regular hours. But nearly every episode digs into juicy technical details about some aspects of winemaking or the wine business, so they are worth the wait.

The production quality is variable. Jim is a winemaker, not an audio engineer, and he often records episodes on location in active wineries, echo-y cellars, at noisy conferences, or in breezy vineyards. But the quality of the guests and the content is never lacking.

This is not a casual wine-drinker's podcast. You will at times experience some chemistry and math, and the words viticulture and oenology. You will learn various technical ways to make lots of different kinds of wines. You will hear the acronyms TA, VA, PV, pH, RS, H2S and SO2. You may need to re-listen to some episodes and take notes.

This is my kind of podcast. This is my grad school.

Some fun tidbits about Inside Winemaking Podcast:

- At the tail end of each episode Jim asks his guests, "What did your childhood smell like?" It may be one of the most random and interesting questions I've ever heard in any podcast.

- The Inside Winemaking theme music reminds me of Buzz Lightyear's Spanish setting.

- Jim does an episode from an improvised burgundy barrel hot tub in which he (drunkenly?) discusses all the technical ways that flavor is created in wine. Now that's how to do science!

Often Very Good Wine Podcasts

The GuildSomm Podcast is high quality in every way. The only reason it doesn't consistently satisfy me is that it is by sommeliers and mainly for sommeliers or others in beverage hospitality. I am not a somm, and have even argued (on behalf of somms) that blind tasting is a huge waste of time and energy. So when the GuildSomm podcast delves into blind tasting, it's a big miss for me.

If you're a somm, though, or interested in the things that interest somms, every episode of the GuildSomm podcast should delight you.

Hosted by Levi Dalton, I'll Drink To That (IDTT) is another very high quality podcast. It features interviews with luminaries of the wine world from around the globe. IDTT is an oral history and audio archive of the wine industry from the mouths of those who had, and continue to have, fundamental influence on the rest of us.

This is why it can be hit or miss for me. Sometimes the personal and historical details of the guests are so deeply explored as to feel academic. It's great history for those who love wine history, but occasionally lacks practical application to how I make and sell wine today.

A new podcast in 2020, Two Glasses In was created by Santa Barbara to highlight some of the big names and celebutantes of the Santa Barbara wine scene. The host, Bion Rice, was CEO and director of winemaking at Sunstone Vineyards & Winery. He knows wine, and he has worked with, or near, many of his guests for many years. It's new, and there aren't yet a lot of episodes, but the quality is high.

Viticole podcast is the brainchild of Master Sommelier and Somm documentary series star Brian McClintic. Brian is passionate, with strong opinions, and I happen to agree with many of his ideas about the direction wine should be heading in terms of organic, regenerative viticulture. Fascinating, at times highly scientific, discussions with smart guests turn this idea-rich wine podcast into something much larger in scope.

The only downside is that Brian hasn't put out very many episodes, and he definitely doesn't put them out regularly.

***

Organic Viticulture Creates Jobs

It's time wineries stop trying to eliminate the number of workers needed to tend a vineyard and bring in a grape harvest. I dare say in fact, despite the recent dire shortages of harvest workers in Sonoma and Napa, that we need to re-envision grape farming as an opportunity to increase the number of people who can be employed. Am I crazy?

Organic viticulture, as it turns out, provides this opportunity, and the potential solution to the worker shortage.

Unfortunately the ability of organic viticulture to create jobs has often been mentioned as one of its down-sides.

You'll hear or read many arguments along the lines of: One worker on a tractor spraying RoundUp can rid the weeds from 20 acres of vines in one day, while it takes a team of workers several weeks to hoe out the weeds from the same 20 acres. The latter, organic approach requires multiple cars driving to and from the vineyard every day for those weeks. So which is worse for the environment?

The RoundUp is worse! It's not even a question. It's a red herring argument.

Just because we eliminate the need for those workers to drive to this 20 acre vineyard doesn't mean we've eliminated the need for them to work. They're going to drive somewhere everyday. They have to make a living.

Why not have them drive to an organic vineyard where they will not have to work with cancer-causing agro-chemicals?

The point is that organic viticulture does often require more work than conventional viticulture, and this has been seen as a bad thing. The reality is that increased labor needs may be one of the best things about organic viticulture.

Aside from the huge benefit to the workers, and the world, in not having to work in a poisoned environment, organic viticulture creates the opportunity for year-round, full-time employment for vineyard workers.

In late winter the vines must be pruned and sprayed. New vines will need to be grafted and propagated from cuttings, and a nursery tended to ensure healthy new vines are ready to replace older vines that succumb to Eutypa or other disease. Repairs to trellising and other vineyard maintenance and cleaning tasks abound.

In spring, the vines may need to be protected from frost. The cover crop may need to be hoed, mowed, or grazed. Shoot thinning and tying must be done. Early spraying begins with Stylet oil or sulfur.

In early summer the workers are busy managing the canopy, pulling leaves, training canes. Workers look for pest and fungus issues, and deal with them as they are discovered. Spraying continues.

In late summer bird netting may be deployed. Fruit may be dropped. Predator habitat needs to be fostered. Irrigation must be managed.

Then comes harvest, and there goes autumn.

In early winter cover crops and beneficial insect habitat may need to be sown. Well deserved rest needs to be taken.

Are there holes in this schedule? Times when full-time vineyard workers may not have too much to do? Yes, possibly, depending on the size of the vineyard.

So why not cross-train vineyard workers as winery workers? Why create a false and - let's be honest - class-based division between vineyard and winery workers?

The same people who spray the vineyards can do the testing, racking, bottling, topping-up, and blending throughout the year. The grape pickers can also do punch-downs, pressing, cleaning, and barreling.

If we want our wines to be truly about terroir, we need to integrate vineyard and winery work, rather than think of them as separate - and hierarchically stratified - parts of the process. If our vineyard workers aren't also working in the cellar, we are merely paying lip service to the truism that wine is made in the vineyard.

It stands to reason that this approach will increase wine quality as well. If your vineyard workers are also your winery workers, they are invested in every step of the process.

Additionally, you allow those crafting your wine to gain expertise by full-time, year-round experience of every step in the winemaking process. How can this not be better for wine quality than having two separate sets of temporary workers - migrant pickers and harvest interns - handling some of the most vital vineyard and winery duties?

I haven't even mentioned the benefit to the workers themselves. They can acquire valuable skills and have security, benefits, and a sustainable income. Rather than take their pay and leave, they can become part of a community, invest in it, and help raise the standard of living there. This is the essence of sustainable wine.

This, we could speculate, will attract more workers to this field. And that may just help with the vineyard worker shortage.

The biggest argument against this is of course one of economics. The average price per ton of grapes in California is right around $850. That's far too low to have many full-time, year-round employees if all you are doing is growing grapes. On the other hand, the price per ton of Napa Cabernet, and the amount that can be charged by a Napa estate winery per bottle, would seem to diminish this economic argument. Of course costs of operation and real estate are much higher in Napa too, so it's hard to say. It will likely depend on the individual winery.

But there are some wineries, like Stolpman Vineyards in Santa Barbara County and others, who are already doing this. It works, likely, because they use a variety of profit-sharing and partnership opportunities with their workers, and they sell their wine for over $25 per bottle, up to almost $100.

Making vineyard workers an integral part of a winery's year round operations does not have to apply only to organic viticulture, but organic viticulture does necessitate more work in and around the vineyard. Why not capitalize on this and see it as an asset, rather than a liability?

***

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

The Secret of Santa Vittoria

I write this in the middle of the 2020 COVID-19 quarantine. So it's possible my entertainment standards have loosened drastically. And of course I'm severely biased in favor of a story in which an Italian town risks everything, even their own lives, to save a million bottles of local wine from the Germans during WWII.

But with those caveats I will boldly assert that I'd recommend The Secret of Santa Vittoria, which you can stream with an Amazon Prime membership, to any wine lover or lovers of movies. It's charming, colorful, sentimental, and delightful.

To paraphrase the movie itself, "It's not a great movie, but it isn't bad."

I hate reviews with spoilers, so I won't recap the entire plot, but here's the premise: the people of a gorgeous hilltop town in Italy during WWII discover the Germans will arrive by the end of the week to take the main source of income for the town - over a million bottles of their local wine - and they must find a way to come together to hide most of the wine and outsmart the Germans.

In the quest to save their wine the townsfolk must toil and sacrifice, test everything they hold sacred, and even risk their own souls. It is a story of bravely holding on to what is most important in life, to a cause that is larger than any individual, even if it means giving up your individual life.

By the end, The Secret of Santa Vittoria makes us ask ourselves, "What kind of people are you?!" What kind of courage do we have? What do we value more than ourselves and our own agendas?

If "wine" fits into your answer of those questions somehow, then you'll probably love this movie.

This movie has a sense of humor. It has a sense of history. It has passion.

And it has wine. Lots of wine.

For a movie released in 1969 it is surprisingly not cringe-worthy for the most part, and could even be commended for some complex and strong female roles (even if it wouldn't quite pass the Bechdel test). There are some frank and unapologetic admissions of (if not celebration of) female sexuality and sexual liberty as well.

The Secret of Santa Vittoria is filmed almost entirely on location in Anticoli Corrado, a town in the mountains east of Rome that is as rich in local, ancient charm as in beautiful scenery. Nearly every shot is delicious.

There are several relationships and subplots that keep the story interesting throughout, and add the real depth to the otherwise comedic tone of the "hide the wine" A-story. If you liked Chocolat (with Juliette Binoche and Johnny Depp), you'll probably like The Secret of Santa Vittoria just as much if not more.

I know I gave caveats, and this isn't a ringing endorsement of the movie. I think that's appropriate to its own sensibilities, which are substantive while understated. But The Secret of Santa Vittoria actually won the Golden Globe for Best Musical or Comedy, and received a couple technical Oscar nominations... so it's got some cred.

I hope you get a chance to see this lovely old movie and let it take you on, if not a quest, at least a charming adventure. It may not change you, but I think it will delight you. I think the point of the movie is that there is something worth cherishing in the simple delights that make up our simple lives, like a bottle of wine.

Or a million of them.

***

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

Farmers Are Cool

I fully realize that me writing the title "Farmers Are Cool" does not make it so. But that's not because it's not true. It is true. Or it can be. And it needs to be.

What makes something cool? What is that tipping point? Is it something in the attitude of the current teen generation? Or is it more classic than that, more pervasive, broader in generational scope?

It may seem like a frivolous question, but what we uphold, culturally, as "cool" is given priority of attention. And farmers and farming are desperately in need of priority and attention. Creating the mystique of "cool" around farming could literally save all of our lives.

When I was in high school and college farming was decidedly un-cool. As I made decisions about what I would study, about what direction I wanted to point my life, farming wasn't even on the list of options.

I grew up around dairy farms and the semi-self-sustaining farms of the Mennonite and Amish in central Pennsylvania. So as a young person, farmers looked like the American Gothic couple and smelled like manure. I was young, creative, hedonistic, ambitious (still am 3 of those 4), so there was nothing desirable in the isolation, hard manual labor, self-denial, and smells I experienced as my local farmers.

I completely lacked imagination.

If I had been able to remove the packaging from the package, it might have dawned on me that farming is almost perfectly aligned to my interests and values. Looking back with all the self-knowledge of hindsight, I realize that farming is a path with so many commendable aspects and so many bodies of knowledge that have been and continue to be fascinating to me, that I likely would have enjoyed taking that path at least as much as the path I've taken, if not more.

I love/d being outdoors. I love/d learning about nature. I love/d preparing delicious meals with fresh and interesting ingredients. I love/d using my body, building strength, getting sweaty & dirty. I love/d being productive every day in a way that is tangible. I love/d nurturing plants and animals and fostering health. I love/d problem solving. I love/d knowing how systems work, being self-sufficient. I love/d knowing where my food and drink comes from.

But farming was un-cool. So instead of using all of the above as my means of making a living, I graduated with a liberal arts degree and worked in office jobs in a city.

Don't get me wrong. I've lived large and made my life interesting. I'm grateful for the opportunities I've had and I've tried to take full advantage of them. I don't regret the life I've lived... but I do regret not being a full-time farmer.

Farming doesn't have to take the form of stinky Puritanical masochism that so many of us, naturally, rejected in our youth.

In Los Angeles there's Ron Finley, the "Ganster Gardener," who has literally built a farming culture on the streets of South Central LA, despite having warrants for his arrest for doing so.

There's Apricot Lane Farm, the subject of the amazing film "The Biggest Little Farm." They built a paradise at the outskirts of Los Angeles using holistic, regenerative agricultural practices that can be an inspiration and model for farms everywhere. When they started they knew nothing about farming. It took them ten years, braving coyotes, firestorms, and bankruptcy.

Farming is for risk-takers, creative people with vision, adventurers.

Some of the most brilliant people I know are grape and marijuana farmers. These kinds of agriculture have such high stakes that it attracts some very cool scientific minds.

Viticulture is, of course, one of my favorite forms of farming. Growing the vines to make wine is as rewarding as having the wine to drink as part of it.

I got into marijuana farming in college. Whenever I discovered something consumable that I loved, I wanted to learn how to produce it.

Our entire, American, culture is designed to make you into a mindless consumer because it is thought that will benefit business enterprise (and perhaps it does, but only in the short term). Being a farmer is a choice to instead be a mindful producer. Being a farmer is actually counter-culture.

Farming psychedelics is another form of farming that I didn't consider when I was younger. Growing mushrooms (even the non-psychoactive kind) is highly technical, and fascinating. Growing Peyote and San Pedro cacti is uniquely specialized. Ayahuasca is an agricultural product, made of a blend of grasses, vines, and barks that can be farmed.

In the modern world we have gained a global mindset, but we've lost the intimate connection we once had to the place from which we actually grow. We are truly ignorant of the most fundamental knowledge about ourselves.

For those who want to re-learn this, you have to unearth a secret, hidden knowledge. You start with something that catches your attention, sparks your joy, and follow it down the rabbit hole. One day you're licking the drips from an ice cream cone, and before long you'll find yourself on an orchid farm in Madagascar by way of helping a cow give birth in New York.

That journey will show you the great connection every one of us has to farming, and the immense impact farming has on not only our personal well being, but on the health of the entire planet.

The great news is that there is huge opportunity right now in farming, because most of it is being done wrong. We are reaping the health and environmental issues that come from decades of poor farming, and we need an entire generation of caring youth to realize there is a better way.

So this is a warning to a generation of young people who are considering their future. Don't be narrow-minded and blinded by prejudice when it comes to farming. It will only make your life smaller. It will only make you less cool.

***

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

Black Is The New Red (Wine)

Wine lingo can be as silly as it is pretentious. But some of the most fundamental language about wine - words we use universally and without question - are the most metaphoric. Take the terms "Red" and "White."

If you actually look at grapes and wine, you'll discover that there are literally zero "white" wines or grapes in existence in this galaxy, as there are zero "red" grapes and precious few wines that may have a tinge of redness to them.

Sure there are purples, garnets, bricks, and rubies in wine, but I challenge you to look more closely. Look deeper. I think you'll find that the wines we call "red" are actually black with some red blended in.

The grapes haven't been known for centuries as Pinot Rouge. They are Pinot Noir - Black grapes. Grenache Noir, not Grenache Rouge.

At Centralas, we've decided to abandon the strange and inaccurate misnomer "red" and call wine by its semantically more appropriate and more interestingly accurate nom de couleur: "black."

We make black wine from black grapes. Pinot Black is one of the grapes we use, Grenache Black is another grape we use (from which we make pink wine). Mourvèdre is a black as black can be.

The use of the term "white" for green and yellow and grapes and the resulting wine makes a lot more sense when you accurately call the complementary grapes & wine "black." It becomes a yin & yang symmetry.

If you choose to continue to use the term "red" you should really switch to using the color-complementary term "green" for white wine & grapes. At least one of your wine colors will be accurate.

Red & White is like apples and oranges - two dissimilar things, randomly associated.

Black & White are meant to be together, attracting opposites, a marriage of love.

Sure Pinot Noir isn't exactly black. But it definitely isn't red. If we're going to be metaphoric, why not make it interesting?

Why Wine Is Unlike Any Other Drink: A Love Letter To Wine's Wildness

Wine is unlike every other alcoholic drink in that it is labeled with a year and a place.

While other alcoholic beverages attempt to replicate themselves identically from year to year - so that you know your 18 year old Glenlivet will be the same as the one you nipped from your grandmother's liquor cabinet when you were 18 - wine announces to us that it will be different from year to year and place to place because it is a reflection of a specific location and time.

Wine embraces change as something inescapable, something you can taste.

Sure, Cognac, Scotch, Bourbon and other liquors are named for a place, but this is really about a local style that its makers must adhere to, rather than a reflection of a specific land's influence on the beverage. Some liquors are dated too, but this is really about how long it was aged, not a reflection of the weather from that particular vintage.

Beer too is a recipe, not a reflection. Follow the same recipe, and you'll get the same beer. For example, brewers go so far as to re-create water mineral profiles to replicate the exact "water ingredient" that was used by monks to make a specific Belgian ale so that the resulting brew will taste remarkably like the original even though made on a different continent, and by the opposite of monks.

The date and place on a wine label signify that wine is special. Wine promotes a concept that is unique in the world of alcohol:

Wine aims to reflect nature rather than control it.

This is why wine is so daunting for many people to understand. Wine is intimidating because drinking a specific bottle doesn't translate to understanding wine. It may not even translate to understanding that bottle.

To understand wine, you have to know where it came from, how it was grown, what grapes were used, what that year was like, how it was made, who was involved, how it was aged, and how everything works together to play a part in what you are tasting now. Even knowing all this, at times when you drink wine it is still somehow greater than the sum of its parts. It transcends all knowledge and is sublime in a way that silences all the thoughts you were trying to apply to it.

And then along comes another vintage and new wines and you have to do all that research again times ten.

Oh, you can identify it in a blind tasting? Naming something doesn't equate to knowing it. A name is just the title of a forgotten story.

Wine is a context, a comprehensive total, a web of interconnection.

95 points? Based on what objective yardstick? That's like trying to explain a human behavior by labeling it either good or bad - it's only helpful as a comfort for the simple-minded.

That is human nature, though. We crave comfort in the face of complexity, security in the face of uncertainty, and when we find something that brings us pleasure we want to repeat it again and again. We want to own it.

Wine is ephemeral.

We want that bottle of 2002 again, but it's gone. Sold out. Consumed. You can only sip on memories of that bottle for the rest of your life.

Without all the knowledge that is necessary to understand it, wine is mysterious, scary. What if I spend $30 of my hard earned cash on a bottle only to find that it brings me no pleasure? There are so many options, so many ways to choose wrong. It can feel like we're Indiana Jones in the Last Crusade, trying to select the Holy Grail from hundreds of goblets.

Deep down in our evolved psyches are centuries of surviving the fickle whims of nature by learning to harness its resources and forces for our benefit, controlling what we can and protecting against what we cannot. Our fears have trained us to avoid the capricious and the irrational.

Wine asks us to let go of all that fear and give in to the wild.

Out in the wild the wind howls through dark forests that conceal dangerous creatures. Shadows are deep, the moon is red, and the storm is on the horizon.

The scariest part is that we feel, beneath everything, that we will find an important part of ourselves out there: A bright-eyed creature who is completely at ease with uncertainty, even ravenous for the taste of surprise.

Of course wine can be made like beer or liquor. It can be made from a recipe with an intent to control nature and beat every aspect of its expression into submission. Nearly every wine in the grocery store is this kind of wine. The date and the place are actually meaningless for these wines - mere artifacts from a time when wine was made wild and true to nature.

We fear change, and these grocery store wines cater to our fears rather than challenging them. Because of that they control the majority of the market.

It can be shocking to transition between this type of wine and the other, between the known and the unknown. People must be prepared mentally for the difference or they will most likely not enjoy the transition.

But the other wine, the wine people mean when they use the word "authentic," is why wine is special. It’s why wine is wine. It doesn't taste of fear. It tastes of the fleeting, uncontrollable, primal currents of time and earth.

This kind of wine - wild wine - doesn't come in a bottle. It comes in a snare that traps your senses with sunlight and wind and sea mist and the spinning of the earth through the universe.

You will only be able to taste it, to experience it as it is intended to be experienced, when you accept that it is change in a sensual form.

Wine is, at its best, unknowable.

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

Organic Viticulture vs. Better Living Through Chemistry?

Crack is vegan.

This is something I say a lot. What I mean is that just because something is vegan doesn’t mean that it’s healthy for you. You can live on french fries, Oreos, and crack and still be vegan. The same is true of the term “organic.”

Organic just means that the substances used must be naturally, as opposed to synthetically, derived. But, as I also like to say, the plague is natural.* Generally we don’t want to spray that on our grapes.

(*Of course, at least in the realm of what is organic, this is an exaggeration because there is a certifying body who must approve a substance for use in organic viticulture. Presumably they would never approve the plague. )

So while I’m ahuge proponent of organic viticulture and think that literally everygrape should be grown organically, I also want to keep “organic”in perspective. I don’t think it is ever good to see only the good,or bad, in something. Most things are complicated.

Which is why, when I encountered the argument cum accusation recently that the objections against glyphosate are akin to the anti-vaccination movement, I felt I had to re-examine my perspective to make sure I was keeping truth as my guiding principle, rather than a one-sided defense of organic dogma.

The argument came in an article by Jamie Goode from a man named Dr. Julian Little: “We are shifting into this post-scientific phase of deciding what is and what isn’t safe,” he says. “You are heading straight down the line of the anti-vaccine movement. Science is no longer seen as a valid currency for making decisions.”

I had to ask, where does the science take us? What do we know vs. believe? Are the principles of organic viticulture wildly detached from sane, scientific findings?

Organic viticulture is ironically, at this point in U.S. history at least, a very conservative approach to agriculture that is mainly embraced by politically liberal farmers. You can see this by comparing maps of conventional pesticide use concentration with political maps showing how the people voted in the last presidential election.

Politically "conservative” Republican-voting farmers are the most “Liberal” in terms of their agricultural practices – that is, they tend to freely use the full panoply of synthetic chemical herbicides, pesticides, and fungicides that have been approved for “conventional” viticulture, even when those substances are known to be highly hazardous and even carcinogenic. That’s crazy liberal!

Organic principles are inherently conservative. There are far fewer options of sprays for organic farmers, and there is an inherent distrust of new synthetic chemicals.

Underlying the best organic viticulture is the principle “Don’t use what you don’t have to.”

If a vine’s health and the quality of the grapes is not affected by grasses and weeds growing amongst them, then why introduce a chemical herbicide into the ecosystem? As “targeted” as an herbicide may claim to be, its aim is to kill plants. And when you spray it around a vine, which is a plant, how could it not affect the vine? Considering that you can just as easily mow, weed-whack, or (less easily) graze the weeds to abate them, why take the chance on an assassin chemical? Especially when the evidence is beginning to show that permanent cover crops may be beneficial to vine health and result in higher quality wines.

Also, the argument that organic proponents are like anti-vaccination people in their rejection of the science around glyphosate is a false analogy.

Over the last hundred years it has been demonstrated that vaccines are necessary to preserve human life. Vaccines are not branded, and are given freely or cheaply to every person, with a motive of increasing the general well-being of the society by eliminating specific nefarious diseases that have no other means of control.

Glyphosate, on the other hand, is a branded convenience, not a necessity of human survival, and it is priced accordingly. There are other, less risky, options for doing what it does. This means that the motivations behind those promoting it are somewhat influenced by capital profit.

We can also see that in many cases science needs time, often lots of time, to determine the relative safety of a new synthetic chemical. Just look at the list of chemicals that were approved for conventional agricultural use years ago and that have now been found to be extremely hazardous or carcinogenic… there are dozens.

This is more understandable when you know that the scientific studies of new chemicals are often funded by the companies that have created, and want to sell, that chemical. The basic mechanics of ulterior motives come into play when analyzing research data. I'm not saying this is intentional, in every case, but it certainly isn't third-party analysis.

Beyond simple ulterior motives, it has become clear that today politics plays a part in how a chemical is viewed, whether it is allowed, the kind of information that is disseminated about it, and the kind of support it receives. We don't have to believe that there are active cover-ups of all the evidence that pesticides are extremely harmful, but knowing that there have been some cover-ups, and the players involved are still in the game and promoting new chemicals, should lead us to a high degree of suspicion of those chemicals.

This track record suggests strongly that we should err, conservatively, on the side of caution when it comes to using synthetic chemicals.

Organic viticulture is not an irrational denial of scientific fact, but really the only sane response from anyone who cares about their own health – not to mention the health of others and the environment as a whole - and from anyone who has been paying attention to the way in which synthetic chemicals have been promoted even when they are known to be very harmful.

Dr. Julian Little is, I should mention, on Bayer’s (the maker of RoundUp) payroll. He's their Head of Communications & Public Affairs for their Crop Sciences division. This fact doesn’t necessarily discredit him, but it certainly casts a shadow of doubt over his motives.

Finding the truth of things is more important to me than being right. So, though I take strong stances on many things, I’m quick to admit I was wrong and change my position when I find out new information that contradicts my arguments. This is one of my most cherished values.

I think we should continue to scientifically test and experiment on glyphosate and other chemicals to determine their efficacy as well as their safety. I just don’t think that they should be allowed to be used in the meantime, before we really know what we’re dealing with.

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

Que Syrah, Sirah?

In most grocery store wine sections (in the U.S.) you’ll usually find bottles of Syrah in the same vicinity of bottles of Petite Sirah. Unfortunately this is probably because the person who stocks those shelves doesn’t know very much about wine. Though it sounds the same, Petite Sirah is not a baby version of Syrah. It’s a completely different grape, known in other climes as Durif. About the only thing they share in common is that both types of grapes are used to make red wine.

Shiraz, on the other hand, is Syrah… just a different name. The Australians call it Shiraz and claim they are being true to the grape’s origin, which is reputed to be the city of Shiraz in southwest Iran… known as the city of Poetry, Wine and Roses. The French apparently wanted to make Shiraz sound a little more pretentious, so they renamed it Syrah. The Californians knew that they could charge more for a wine made from a French sounding grape, so they stuck with Syrah for the most part. Since they are grown upside down, the Australians may just like to be a little contrary too. They also produce Durif.

Can all of this get a bit confusing? You bet shiraz.

Is Wine A Luxury Product?

Collectors items - vintage ruby red wine and copies of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam

"Dry January" strides virtuously and purposefully off the end of the calendar month into, we assume for some, wetter months ahead. Instead of partaking - oxymoronically - in abstinence, I used this arbitrary stretch of time - between Winter Solstice debauchery and the beginnings of late-winter cabin fever revelry (kicked off in the U.S. by the Superbowl, perhaps) - to be thoughtful about wine.

So while you were strenuously keeping your New Years Resolutions for the past month, I was vigorously wrestling with the question of, What is wine's place in human life and culture?

Of course that required the drinking of wine.

My conclusion is that it depends very much on the specific human culture about which we are talking. Wine tends not to be highly regarded in Muslim cultures, for example. While for Christian cultures it can be regarded as a sacrament - sometimes only a sacrament. Those would seem to be polar opposites, but may in fact be bound much more closely than either religion would like to believe.

What strange form of extremism is the idea of abstinence. It seems, to me, an unhealthy dualistic conception whose flip side is addiction. That which is fetishized as a tempting demon to be avoided, unavoidably becomes the scapegoat of human weakness. Those caught in the pull of the heads-or-tails paradigm they have internalized fail to see that the hub at the center of this duality is themselves.

So I don't think it is possible to talk about wine in general, as it regards culture. I can only talk about the personal culture that I humbly embrace, and love.

My name, Adam, is from the Hebrew language and is rooted in the color red, but also resonates and alludes to the earth, dirt, dust. It is sometimes translated as meaning "red earth." But in the context of its allusions it probably would be more accurately translated as "mortal." As in "from the red dirt and dust we come, to the red, bloodied earth we return." This becomes especially significant since "Adam" is the Biblically applied moniker for all humanity. We are, each and every one of us, Mortals.

Both the red earth and mortality have significance in my personal wine culture.

I was raised with the Christian Bible and without wine. So I found my first inspiration in the biblical treatment of wine. For all the Puritanical prohibitionism that sprang from biblical religious traditions, the Bible itself seems to uphold wine as a significant, and significantly positive symbol.

At the beginning of the Bible, early in the book of Genesis, we get the story of the Great Flood and Noah's Ark. The denouement of this story was left out of my childhood, but now holds a special place in my heart.

It isn't often put in these terms, but the world after the great Flood would have been literally post-apocalyptic. Noah and his family would have witnessed the deaths of everyone they had ever known except each other. The bodies of the dead would have been swirling in the flood waters for weeks. Now the waters would have receded, leaving the macabre flotsam rotting on the ground to be pecked by crows. The earth would have been wiped clean, and the scene, as Noah descended from the ark, would have been like the aftermath of a world war in which no one survived.

Noah's first act? He immediately planted a vineyard. (Which, btw, means he had brought vines on the ark. Good foresight.)

Of course I've come to see the need to read these stories symbolically. Was there really ever an actual historical global flood, an ark, and a man named Noah? Doesn't really matter. Think of this as a form of reverse sci-fi. Instead of telling us where we might be headed, it aims to tell us how we got to where we are. Humanity got a reboot in the form of global annihilation. Only one family got the early warning and survived, and as they emerged from their fallout shelter they looked around and said, "This calls for some wine. ASAP."

Noah planted a vineyard to make wine before he planted food crops. The story seems to say that wine, and specifically its ability to diminish life's darkness, to numb the pain so to speak, is a more important form of sustenance than food.

If I was answering the question of "Is Wine a Luxury Product?" using the book of Genesis, the answer would be "No." Wine is an urgent need in the face of the sometimes painfully unavoidable elements of life.

Isaiah, the prophet, once foretold of the Utopian future that Yahweh would bring about by saying:

On this mountain the Lord Almighty will prepare

a feast of rich food for all peoples,

a banquet of aged wine—

the best of meats and the finest of wines.

"A banquet of aged wine" is the preeminent symbol of Utopia? Yes, Isaiah, I heartily agree.

In the Song of Songs (or Song of Solomon) - the Romeo & Juliet book of the Bible - wine gets many mentions and comparisons to love. Here is one of my favorite:

And the roof of thy mouth like the best wine for my beloved, that goeth down sweetly, causing the lips of those that are asleep to speak.

Then of course we get to the book of John in the New Testament, and we learn that Jesus' first miracle ever was to turn water into wine when the wedding that he was attending ran out. I won't break down all the symbolism and allusions packed into this story (though it will be the first sermon in my future Wine Church), but suffice it to say that it introduces the central character with the idea of transformation. The story of Jesus' first miracle is a micro-story of the meta-message that within the mundane lives the extraordinary.

The trappings of wine marketing and the wine industry - the bottles and labels and sommeliers and fancy glasses and beautiful wine tasting rooms and wine bars and Instagram feeds and podcasts - belie the fact that wine is this little miracle of transforming water (and earth and sun) into something that can change you.

As my personal culture matured beyond my Christian upbringing, I discovered another ancient source of wine inspiration: The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam. A "ruba'i" is a poetic quatrain, and Khayyam wrote quite a number of them (LXXV to be exact), saturated with wine metaphors, and assembled into a meditation on mortality. He was born almost 1,000 years ago in ancient Persia - now Iran.

Omar Khayyam says in his Rubaiyat:

Ah! My Beloved, fill the cup that clears

Today of past Regrets and future Fears -

Wine's ability to change our moods is pretty special. It is, almost literally, bottled sunshine, and can bring a glimmer of light into a dark time.

Because of this I think of wine as more like a story than a product. Every bottle is a little condensed version of life. Its consumption is a cycle, like listening to a story, that makes us feel and helps us cope with the larger, inescapable cycle from which it, and we, grew. There's something important and ineffable - even magic - in that.

Omar Khayyam also says:

I often wonder what the Vintners buy

One half so precious as the Goods they sell.

Wine is too inextricable from the human culture from which I've grown to be considered a luxury. Yet I wouldn't call it a grocery item either. That seems to take it for granted, and I don't even think we should take water for granted.

Is wine a luxury product? No. Wine is not a luxury product. But it makes my life luxurious.

***

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

The Evolving Science of Organic Viticulture

How we farm wine grapes constantly evolves as we learn to adapt to new knowledge, new climatic events, and new pest pressures. It’s not static. When we commit to organic viticulture, then, are we locking into only one option? Are we doing the same kind of viticulture year after year, despite annual variations and new problems?

If I’m a typical conventional winery owner, I may feel that organic viticulture ties my hands, and it costs more. If I choose to farm my grapes organically, I think, I’ll limit the tools I have to keep the vineyards healthy and, ultimately, sustainable.

There are several arguments here to parse out, and they are worth addressing individually:

1. Organic viticulture is static - FALSE

Organic viticulture evolves continually, both in products and in processes. It wasn't very long ago that copper and sulfur were the only sprays available to the organic grape grower. Now copper is being removed from many organic programs due to its toxicity, and sulfur spraying is being reduced due to the availability of newly approved organic options - like Stylet Oil, potassium bicarbonate, Romeo, and Sonata.

Additionally, we've learned how to take a holistic approach to vine health, rather than just a prophylactic one. We've implemented insectuaries and cover crops to build a diverse and balanced ecosystem which keeps pests in check. We've implemented different ways of cultivating internal vine health, through soil building and vine "vaccines," to enable vines to resist pathogens naturally.

It's important to understand that the percentage of organic viticulture has been very low, and is only recently starting to increase. Because it was such a small slice of the pie, we dedicated a respectively small amount of resources to research and development of organic products and process, so of course the organic options were slow to increase and improve. As the percentage of vineyards that are being farmed organically or biodynamically increases, we will see more resources dedicated to R & D, which will provide more options, which may reduce some of the fear of "going organic," which will lead to more organic vineyards... and the virtuous cycle will continue to grow.

Also, organic viticulture doesn't do the same thing year after year. At its best, organic viticulture cultivates the vineyard within an entire ecosystem that is nurtured and encouraged to naturally adapt to annual variations.

The argument that organic viticulture is "static" or non-adaptive comes from a mind-set that sees humans vs. nature, where nature must be dominated and controlled by use of chemical tools. New problem arises? Spray a new poison on it. Organic viticulture, on the other hand, sees that when properly cultivated an ecosystem has its own tools to take care of itself. Organic viticulture empowers the vineyard to manage itself, so to speak.

2. Organic viticulture has limited tools - TRUE FOR NOW, AND THAT'S GOOD

Yes, there are a huge number of pesticide sprays available to conventional grape growers - maybe twenty times as many as organic pesticides, or more. And many of those conventional pesticides are highly toxic, hazardous to human, plant, and animal life, and even carcinogenic or or worse and should be banned outright.

The number of organic options is on the rise as well. As mentioned above, the growth of organic options has been stymied by lack of interest until recently. That number is on the rise now, and will continue.

But this argument also presumes a "quick fix" approach to viticulture that is actually part of the problem. Our forebears didn't have many tools in their agricultural arsenal, yet somehow they managed to develop dozens of vitis vinifera vines that were adapted to their climate, able to be grown without irrigation, and resistant to the local disease and pest pressures. They did this over hundreds, even thousands, of years of breeding, hybridizing, and selecting grape varieties, often from those that were native to that particular area, to achieve delicious tasting AND hardy grapevines.

Rather than wisely following that example, however, we yanked the vines out of the area to which they had adapted for thousands of years and planted them in a foreign climate with radically different diseases and pests. Well of course that didn't work - and the vines were ravaged by all of the new challenges to which they haven't had time to adapt. So what was our solution? Poison the earth to sterilize it of anything that might present a challenge to these foreign plants.

We continue to employ this same approach today. We want to grow native European grapes in America, and we want simple, immediate solutions to problems that were originally solved over millennia.

3. Organic Viticulture is Unsustainable - FALSE

Organic viticulture limits the "tools" we can use for a quick fix because the real fix - the real path to vineyard health - is not something that can be sprayed on a vine - it's cultivating vines that don't need to have something sprayed on them.

Ironically, the arguments above are made as often by wine growers on the West Coast of the U.S. as on the East Coast. Yet somehow there is an organic winery in Virginia - a place as foreign to the Mediterranean climates of the West Coast and Southern Europe as can be. The existence of even one organic winery in Virginia makes the dearth of organic vineyards in a place like Washington State - while understandable - inexcusable.

While conventional viticulture may provide short-term benefits to a cash crop, it is clear that this kind of agriculture, and this kind of thinking, is unsustainable. The health of the vineyard is inseparable from the health of the ecosystem and larger environment in which it grows, and its becoming clearer that conventional agriculture is weakening and sickening our global environment.

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

Aging Wine: Is Your Wine Helen Mirren or Keith Richards?

“Like a fine wine, I get better with age.” It’s an old adage that sounds nice, but we all know examples to the contrary. So how do you know if your wine is a Helen Mirren – one for whom the years only serve to undress her subtle beauty, grace, and style – or a Keith Richards – one that you wish had kept his clothes on? The key is that not all wines are “fine.” In fact most aren’t.

The truth is that 85-90% of wines produced worldwide are at their peak upon release and are meant to be drunk when you purchase them. As tastes are becoming more and more influenced by a “new world” style of wine, that percentage is growing. Life is uncertain, and people want good wine now, not in 20 years when we’ll all be refugees in Antarctica. Yes, these non-fine wines can hang around for a year or two, and sometimes longer, but it’s not going to make them taste any better. And depending on how you store them, that extra time may actually make them taste worse.

So how do you know if you have a bottle from the other 10%, the kind that are designed to age? Here’s a good rule of thumb: if it’s under $25, go ahead and drink it. Those “fine” wines tend to be on the high end of the price scale. Here’s another adage: “Wine does improve with age. The older I get, the better I like it.”

- Originally posted on July 20, 2007

Buty Winery - Rocking It

I'm jealous of Nina Buty (pronounced "beauty") - the founder of Buty Winery - for several reasons. Her "Rockgarden" estate vineyard is ten prime acres of organically farmed vineyard in one of the most unique AVA's in the U.S., if not the world - The Rocks district of Milton-Freewater. She turned a liberal arts degree into a successful career of creating delicious wines. Also, she lives in a place where it snows in winter.

But it's the story of her wine that interests me.

Story is such a buzz word these days. In marketing and sales - we are asked to tell the story of our brand, our business. We are told that to be successful we must have a good story.

In the context of wanting to sell - whether we are selling wine or anything else - we may have lost sight, though, of what Nina Buty calls the "primal need" of story. We may tell our story, Buty says, but it takes on a life outside of us and beyond us.

Stories are encapsulated miniature life-cycles. Something is born, it struggles, it triumphs or fails (maybe more than once), and it dies. Again and again we repeat this cycle - in pictures, in words, in wine - like a chant, like a lifelong mantra.

A story is a mirror with a warning that "things are closer than they appear." It's a reminder, a way to experience a condensed form of the very thing from which it arises. It helps us cope with - by laughing at, crying at, and seeing the beauty in - the inescapable.

For Nina Buty, wine is a story unto itself. It tells its own story.

If you read around the Buty Winery website a bit, you'll see the word "Interconnection" in one form or another more than once. This word is at the heart of the Buty story, and why I'm such a fan of Buty - beyond, of course, my covetous nature.

She sees the potential for a bottle of wine to make a connection between the land and the people who work it and the people who, far away from that land, taste its story in the bottle.

Nina Buty has built Buty Winery with this intention. She makes her wines to reflect the "weaving of things" - a mystical, but not at all far-fetched, conception of the interconnection of all things. That is why, she asserts, you can taste what she calls a "family resemblance" in all of the Buty wines.

"Places of nexus - of not just touch, but overlap - have always been fascinating to me," Buty explains. "The winery is one of those places."

Buty Winery is located, appropriately, in Walla Walla - a unique AVA that overlaps two states: south-east Washington and north-east Oregon. Climatically, Walla Walla is also unique - it is the furthest north occurrence on the planet of a hot-summer Mediterranean climate.

This climate leads to a place, and wines, of extremes. Summer temperatures are often above 100 degrees F, but the biggest challenge in the vineyard is actually winter-kill and bud damage from cold freezes. When everything aligns, the resulting wines can be lush and ripe while also elegant, complex, and age-worthy.

While the Buty tasting room and winery are located in the town of Walla Walla in Washington, and most of the vineyards from which Buty sources its grapes are the "grand crus" of Washington, Buty's Rockgarden estate vineyard is in Oregon in a unique sub-appelation of the Walla Walla Valley AVA called "The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater."

Where so many AVAs can be so large as to be meaningless, or determined loosely by non-unique or non-distinctive collectives of terroir, The Rocks is one place in the U.S. that is absolutely geologically unique. Buty describes The Rocks as a riverbed six miles square with cobblestones up to 500 feet deep. The cobblestones are the remains of an ancient alluvial fan created by the Walla Walla river, and range in size from small russet potatoes to footballs. If this brings to mind the galets of Chateauneuf-du-Pape, you've made the connection to the most common comparison The Rocks gets. Just add more rocks.

This kind geology leads to mineral rich, extremely well drained "soils" that cause the vines to root deeply and the wines to taste distinctively. The basalt cobblestones that line the vineyard rows absorb and radiate the sun's energy as well as reflect it up into the vines, allowing for earlier budding and greater ripening.

Buty saved and planned for years to be able to purchase 10 acres in the highest and most prime section of The Rocks to establish her Rockgarden estate vineyard. "We planted the vines with a crowbar," Buty reminisces.

Washington state has the lowest percentage of organically or biodynamically farmed vineyards of any western state, but Buty chose to farm organically from the beginning. It was precious land to her, and she saw Buty winery as its steward. "It was where my children were going to play, and where we were going to employ people to work."

That personal connection to the land, and interconnection between it and all of our lives, is a common reason vineyard owners give for choosing to farm organically. Though Rockgarden continues to be farmed organically, Buty only got the vineyard certified from 2010-15. The knowledge that she was farming responsibly and cleanly was more important than the piece of paper she could use for marketing purposes.

It's not cheap to farm the Rockgarden. The stones wreak havoc on equipment. Suspensions are soon shot. It is a physically strenuous vineyard to farm. The money she saved by not getting certified each year Buty put back into the vineyard.

When I pushed Nina Buty to talk about why she thought more vineyards in Washington state weren't organic or biodynamic, she gave one of the most thoughtful excuses I've ever heard, and one that will definitely be the sole subject of an entire future post:

How we farm is always evolving, she said. We are changing and adapting to new knowledge, new climatic events, and new pest pressures. It's not static. But committing to organic viticulture feels like locking into only one option. There's a fear of doing the same kind of viticulture year after year, despite annual variations.

If I'm a typical winery owner, Buty speculated, I feel that organic viticulture ties my hands, and it costs more. If I choose to farm organically, I'll limit the tools I have to keep the vineyards healthy and, ultimately, sustainable. If there isn't a market demand or reward for it, then what's the incentive?

Of course I think there are answers to these arguments (and I'm trying to promote that market demand), and Buty likely does too since she chose to farm her estate vineyard organically. But she displays such an empathy for and camaraderie with her Walla Walla wine community that she gives full credit to those who choose to farm differently.

"Camaraderie" is the word Buty uses to describe Walla Walla, actually. It's not shellacked, she says. It's pretty real. There's a high level of wine knowledge and a small population. That leads to great access. Winery owners can often be found pouring their own wines in their tasting rooms.

"There's no traffic and lots of parking," she adds with chuckle, knowing how to tease a Los Angeleno. Oh, and there are something like two distilleries, four breweries, and 20 wineries within four blocks of the Walla Walla airport.

Is Walla Walla sounding like booze heaven to anyone else?

As a footnote to this article, a week after my initial phone interview with Nina Buty I read in the wine trades that she had sold the Rockgarden estate vineyard. Buty Winery will continue as it has, and the new owners have said that they intend to continue to farm Rockgarden organically. Buty made the choice to sell for many reasons, mainly that it was the right opportunity at the right time for her family.

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

How Do We Determine The Price of Centralas Wines?

What to charge for Centralas wines is a question that we have pondered and wrestled with for months. After struggling with innumerable calculable and intangible factors, we finally realized the decision was easy. We had to price the wine to reflect the mission of Centralas.

We have priced Centralas wines so that we can have a sustainable business while also providing an extreme value to lovers of ultra-premium wine. Because of the costs of producing high quality, no-expense-spared limited quantity wines from exceptional organic and biodynamic vineyards, we can never compete in price with the mass produced, chemically tainted, manipulated wine-beverages that are available in the grocery store. However, if you compare our wines to others in their categories, you'll find Centralas wines to be priced well below market.

Why would we under-price our wines and there by undercut our potential profits?

I joke that I had a career of over 15 years in non-profits, so that's my model for running a winery.

Within that joke is a lot of truth.

We want our wine to be affordable for the majority of us with ordinary means, because we want to spread the values of organic and biodynamic winegrowing. Those values shouldn't be for the wealthy elite. (Though we hope the wealthy elite will take advantage of our below market prices and make our wines their daily pours.)

We aren't doing this for the money. We're not even really doing it to sell wine.

Yes, we love wine. But what we want to spread is connection.

That's our mission - to promote connection. Connection to the earth. Connection to each other.

Wine just happens to be the perfect way for us to do that. Organically and biodynamically grown wine, that is.

We want to make your support for Centralas the easiest and most enjoyable way for you to support a cleaner, greener, and more connected world.

We believe that each of us has a lot of power to make change by taking simple actions every day. How we spend our money is the most important form of voting we have. It's important because what you choose to drink and eat is a vote you make every day, and it determines the direction of an entire agricultural industry - the industry that may have one of the greatest impacts on our environment and our world.

Therefore we have priced our wine so that it can be a regular choice, not just a special occasion.

But with wine that promotes this much positive change, tastes this good, and at these prices - every bottle is a special occasion.

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

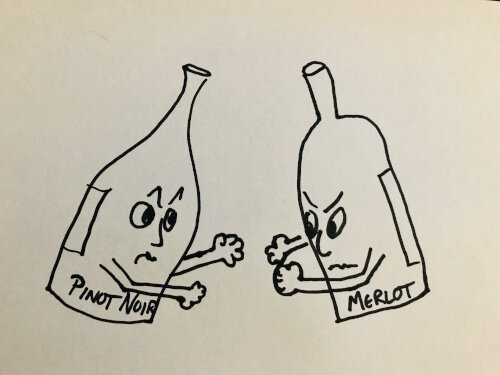

Pinot Noir vs. Merlot

Miles, from the movie Sideways, refused to drink Merlot (with now infamous emphasis). Within a year of the Academy Awards where Payne & Taylor took home the Oscar for screenwriting adaptation for Sideways, Merlot sales had dropped over 40%. Pinot Noir on the other hand, Miles’ favorite, is enjoying an unprecedented heyday. Yes, this shows the power of movies to influence our lives, but unfortunately it also shows that the subtlety of good storytelling is lost on the general public.

Miles hated Merlot. He also disparaged Cabernet Franc. But remember his precious 1961 Chateau Cheval Blanc, the wine that was a metaphor for Mile’s life, that he finally guzzles at the end when he has learned whatever it is he learns? It is a little known fact, except among wine geeks, that the Cheval Blanc is a wine made of a 50/50 mix of, you guessed it, Merlot and Cab Franc.

It was a brilliant move on the part of Payne & Taylor, to underline the contradictions inherent in their complicated protagonist. One of those juicy tidbits that makes Sideways a movie to revisit. Unfortunately devastating to California Merlot producers.

Merlot is the most predominantly grown grape in Bordeaux. The hands down most expensive and revered wines in the world, the Bordeaux first growths, are made with differing mixes of Merlot, Cab Franc, Cab Sauvignon, and a couple other grapes. Lucky for the French, they name their wines after the location from which they are produced rather than after their varietal, so the unwitting American Merlot snob wouldn’t be deterred from spending a small fortune on Merlot. It’s not Merlot… it’s a Chateau d’Whatever.

Is my point that Merlot is actually better than Pinot Noir? No. The moral of this story is that prejudice is always silly. Great wines come from every family of grape, and your particular tastes on any specific occasion often play the most important role in determining if you will love or hate a wine. So go out there and drink some #@%ing Merlot!

Centralas Wine Recommendation:

Try some Frog's Leap Merlot. Full of hypocrisies and contradictions, rich with metaphor and insight, this vino will appeal to both the undiscerning layperson and those with a taste for subtlety. Pairs well with In-&-Out and an unprejudiced heart. (It's also dry-farmed and biodynamically grown!)

- Originally posted December 20, 2007

For more about how the movie Sideways changed the wine world forever, check out our post You'll Never Be Able To Drink That Wine Again.

Please use this form to join our mailing list if you want to support positive change in wine and the world, as well as be the first to get access to our new wine releases and special offers.

"Approachable" Is A Euphemism

Wine lingo can be as esoteric as entertainment industry gab, and it tends to sound twice as pretentious. A “hot” wine is overly alcoholic. The “robe” is the color of a wine. A “varietal” is the kind of grape from which a wine is made. A person who loves wine? Yes, a “wine-o,” but also, technically, an “oenophile.” How do you even pronounce that?

The descriptors that are the most fun personify wine. At a wine tasting you might hear people nod and agree, with a straight face, to a wine description such as “rich and well built, with nice legs, a sexy mouth feel, and a silky back end.”

One of the silliest words I’ve heard used to describe a wine is “drinkable.” Really? Because I assumed this was meant to be poured down the drain. That’s why I’m spending the twenty bucks. My drain needs a wine rinse. Even better is “very drinkable.”

But the term I find to be the most insidiously pretentious is “approachable.” I can’t tell you how many times I’ve heard this tossed around in wine shops, in wine magazines, and even on wine bottles. What bothers me about this word in particular is that it is used almost exclusively as a signifier.

And what does it signify? Usually that the person speaking it thinks that the person hearing it has very little knowledge of and therefore pedestrian tastes in wine. Or it’s code for those in the know that a wine is not sublime.

What it means, essentially, is that this wine appeals to the undiscerning masses. It’s uncomplicated, unrefined, fun. Yes, you’ll enjoy it. Everyone does. In other words, “approachable” is a highfalutin way of saying – if I may coin a new wine term – “slutty.” Take it as you may, at least we’ve left the realm of pretense… and at Centralas, there’s no shame in a wine that goes down easy.

- Originally posted August 20, 2007

The Best Wine You Will Ever Drink

Substitute the word "tea" with "wine" and you may gain more respect for Jet Li.

Yes. Yes, I did just embed a clip of the tea scene from Jet Li's Fearless.

The simple but profound point that this gem of a scene, from a surprisingly decent kung fu movie, makes is that the quality of something is most often subject to the mood of the person experiencing it. If you substitute the word "wine" each time the word "tea" is used in this scene, you'll see why this clip is relevant for us wine drinkers.

The quality of the taste of any wine you drink will be drastically impacted by your mood and the setting when you taste it.

Yes, you can go to great lengths to eliminate variance when tasting wine. You can always taste wine in the same white room, at the same temperature, in the same type of glass, open for the same amount of time, from the same size bottle, while wearing the same clothes, at the same time of day, after meditating for 15 minutes on emptiness. And then, maybe, you'll eliminate the variables that could prevent you from tasting objectively.

However, no sane person drinks wine this way.